Sipping Culture: Rediscovering Teahouse Storytelling

Can you picture yourself in a theatre, sipping tea and savoring traditional sweets, all while being spellbound by a storyteller's tales? This unique experience isn't a modern innovation — it harks back to China's centuries-old tradition of teahouse storytelling.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★★

TAIPEI, Taiwan — Over three thousand years ago, history was made when a leaf from a nearby shrub fell into the boiling water of Chinese Emperor Shen Nong. This fortuitous incident is believed to mark the very first discovery of tea. As centuries passed, tea transformed into an indispensable facet of Chinese culture, sometimes shaping the course of history.

As the number of tea enthusiasts grew, tea-related businesses flourished, closely intertwined with the burgeoning commerce and the emergence of a middle-class society. Innovations in tea processing and brewing methods further fueled this growth. And the earliest tea houses can be traced back to as early as the Song dynasty (960—1279).

Over time, teahouses went beyond merely selling tea; they served as multifunctional establishments, offering dining services, and serving as communal centres for local communities. At some point, teahouses also played a crucial role in the development of China’s performing arts scene functioning as an entertainment venue. Storytelling sessions known as pingshu first surfaced in teahouses during the early years of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912).

In teahouse storytelling, or chaguan pingshu, a solo narrator captivates audiences with vivid storytelling, expressive gestures, and lively facial expressions. Armed with nothing more than a wooden block and a paper fan, the storyteller weaves enchanting tales that come to life within the teahouses’s intimate setting.

At a time when teahouse storytelling and Chinese opera were popular forms of entertainment, patrons would visit teahouses to enjoy a cup of tea — often coupled with melon seeds — while listening to storytellers narrate a wide array of tales, spanning from literary classics to eerie stories like those found in Liaozhai, known in English as “Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio”.

Tea artisan brews Taiwan’s baozhong tea — a lightly oxidised tea with floral notes — for the audience to drink during the performance.

The first person to introduce pingshu to the Manchu people was the legendary storyteller Liu Jing-Ting (柳敬亭) hailing from Jiangsu, a coastal Chinese province to the north of Shanghai. In his biography penned by the scholar Huang Zongxi, Liu's artistic mastery is depicted as having transcended words, evoking emotions of sorrow and joy in listeners even before they were spoken, thus exerting a profound influence on their sentiments.

In Manchurian, storytelling is known as “julen be donjire”, which translates to “oral novel”. The essence of storytelling lies in the ping, or commentary — the storyteller must not only narrate historical anecdotes but also incorporate their unique point of view and commentary, thereby imparting ideological concepts to the audience.

My initial encounter with this unique art form took place over a decade ago at the Laoshe Teahouse in Beijing, where I was introduced to the captivating experience of teahouse performances. Sadly, the tradition of teahouse storytelling is fading away in Chinese-speaking cultures, succumbing to the rise of new entertainment forms and shifting cultural preferences. In Taiwan, this beloved tradition hasn't survived, and the idea of teahouse storytelling isn’t widely known.

However, on a sunny Sunday afternoon in July, I had the opportunity to attend a live teahouse storytelling event organised by Taipei Quyi Tuan (台北曲藝團). This Taiwanese troupe is committed to popularising traditional Chinese stand-up comedy, often referred to as “cross talks”.

Accompanying the tea, a selection of traditional sweets such as mung bean cake (left), sweet glutinous rice (middle), and dried mango slices ( right), were served during the latter part of the performance, following the intermission.

Before the show began, the audience was servied tea by a skilled tea artisan, who prepared Taiwan's renowned baozhong tea — a lightly oxidised variety known for its delightful floral notes. We had the pleasure of savouring this tea throughout the performance.

After the intermission, a selection traditional sweets was brought forth, featuring mung bean cake, sweet glutinous rice, and dried mango slices. These sweet treats harmonised perfectly with the tea, which carried a subtle hint of bitterness from its tannin. As we savoured the tea and indulged in these Chinese sweets, it felt like a journey back in time, relishing the charm of old-fashioned way of entertainment.

The two-hour program encompassed crosstalks and “shu lai bao”, a rhythmic storytelling style accompanied by clappers. Amid this variety of performances, my personal favourite was the closing storytelling session, presented by the troupe's leader and event host, Yeh Yi-Chun. Yeh presented two enthralling tales from the Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, a collection comprising nearly 500 captivating stories that stand as a pinnacle in Chinese ghost literature.

Unlike usual practices, this storytelling session was enriched by the pipa player, Chang Shih-Neng, whose music added vibrant hues to Yeh's narration. This harks back to the early days of this artistic tradition when pingshu involved not only spoken narration but also singing. During these performances, the primary musical instrument used was the pipa, a traditional Chinese lute.

Yeh Yi-Chun, leader of the Taipei Quyi Tuan, gives a “pingshu” performance.

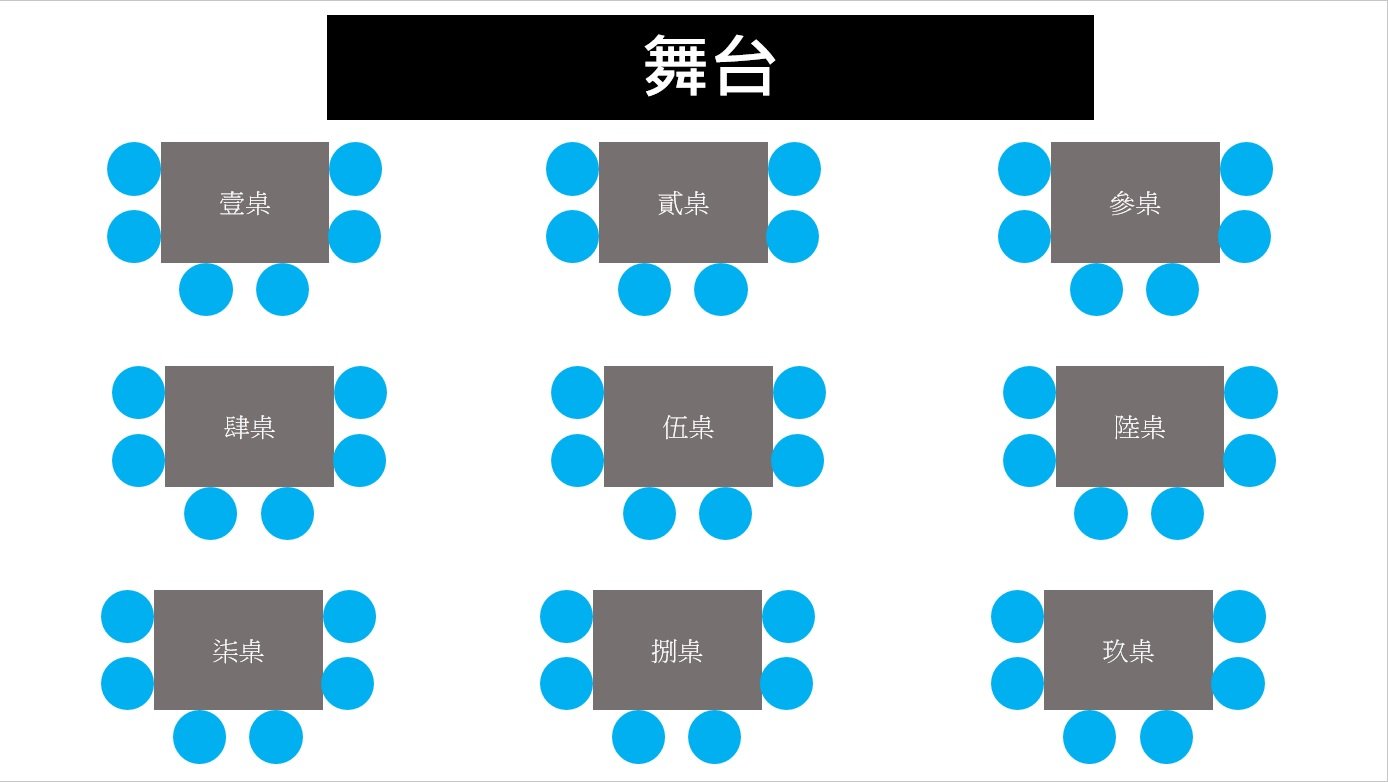

In addition to the program, tea and sweets, the theater's seating arrangement within the Multifunctional Hall at the Taiwan Traditional Theatre Centre further shaped to the audience’s unique experience. Despite being designed for 120 spectators, only 54 seats were made available; these seats were arranged with six audience members around each of the nine tables, creating an intimate and spacious viewing experience for all attendees.

This isn't Taipei Quyi Tuan's first attempt to host such events. In the past, the troupe used to host an annual event known as Taipei Dawancha (literally “Taipei’s Big Tea Bowl”), where audiences could enjoy tea at vintage wooden tables and chairs while immersing themselves in the art of spoken word. However, the tradition hit a pause when the historical Red House Theater in Taipei replaced its old furniture with audience seats in recent years. It turns out that reviving such traditions demands not only the desire for preservation but also for the stars to align just right.

Teahouses have been instrumental in shaping the development of storytelling performances, but it seems that this time-honoured tradition has, ironically, adopted an “avant-garde” identity, similar to how the relentless chase for speed has turned “slow living” into a fashionable lifestyle choice.

Seat arrangement of “Tea Gathering” event hosted by Taipei Quyi Tuan at the Taiwan Traditional Theatre Centre. Image courtesy of Taiwan Traditional Theatre Centre.

Tips for wanderer — where to see Tea Gathering?

If you're eager to experience teahouse storytelling, keep an eye out for updates from Taipei Quyi Tuan or the venue host, Taiwan Traditional Theatre Centre, as they may host similar events in the near future.

Reference:

Qiu, Yuan. "Qīngcháo de rénmen zài cháguǎn lǐ gàn shénme", 2019, March 22, https://www.jiemian.com/article/2977459.html. Accessed Aug 8, 2023.

Taipei Quyi Tuan’s Tea Gathering was staged at the Taiwan Traditional Theatre Centre on July 30, 2023.