Wandering Through the Bunun Tribe: Stories, Scents, and Flavours

Just a half-hour drive from Sun Moon Lake, the people of Danda Bunun invites you on a unique journey — beginning with a warm welcome ceremony and a toast to the heavens, the earth, and the Bunun ancestors.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

Created by Laung Mankoko, this giant sculpture, titled Qudas, sheds light on the vital role elders play in preserving and transmitting Bunun traditions.

NANTOU, Taiwan — From the Sun Moon Lake, we travel south to the Tamazuan Village, located upstream of the Zhuoshui River, Taiwan’s longest river. This area, known as Danda, is home to to an indigenous settlement primarily inhabited by the Bunun tribe.

The Bunun, meaning “people” in their language, are a highland tribe residing at elevations between 1,000 to 2,000 metres. Having traversed the entire Central Mountain Range, they proudly call themselves the “guardians of the Central Mountain Range,” with Nantou County as their main area of residence. Today, five of the six Bunun groups remains, and the community we’re visiting belong to the Dan group.

Upon arrival, we meet our host and guide, Laung Mankoko, Chairperson of the Danda Bunun Ecotourism Association. He begins by giving guest a Bunun name, encouraging us to use it when introducing ourselves to other Bunun people or indigenous friends in the future. Mine is Uli, a common Bunun name for girls.

Laung welcomes us with a small ritual, singing a song in the Bunun language. The song announces our arrival to their ancestors and also blesses our entry into the mountains. We’re then guided to toast millet wine to the heavens, earth, and ancestors — a gesture that moves me deeply, as such a connection is often absent in urban life.

Suddenly, the ceremony is interrupted by the crack of a fire gun shot into the sky — my first time seeing a gun fired so close. When I asked, Laung explained that they had forgotten to fire the gun at the start of the ceremony.

Laung shares that, in addition to being an advocate for his tribe, he’s also a sculptor. In fact, not far from where we stand is a five-metre giant he crafted entirely from scratch.

Facing the Danum Qalavang (the Bunun name for the Zhuoshui River), this sculpture, titled Qudas (meaning “elder”), embodies the esteemed role of elders in Bunun culture. It stands as a powerful symbol of the wisdom, experience, and skills handed down through generations — a silent guardian of their heritage.

Laung Mankoko, Chairperson of the Danda Bunun Ecotourism Association, welcomes us with a Bunun ceremony.

Entrance to Dili Village, known as Tamazuan in Bunun.

The Stories: Seeing the World through the Bunun’s Lens

We follow Laung to the heart of Tamazuan village, whose name means “rooster” in Bunun language. Legend has it that the area was once a mosquito-infested swamp. One morning, a large rooster appeared, and from that day on, the mosquitoes vanished, giving the village its name. While, Tamazuan is now considered the village’s old name — officially replaced by Dili Village — I’ll refer to it as Tamazuan in honour of the Bunun tradition, which this article seeks to celebrating.

Here, the community centres around Renhe Elementary School. Its outer walls are adorned with vibrant mosaics and low-relief carvings that depict Bunun folklore.

According to legend, a giant python once blocked the Zhuoshui River, causing a devastating flood across the land. People and animals fled to the summit of Yushan to escape but were left stranded without food or fire. Spotting smoke rising from Ludun Hunul (the Bunun name for Mount Xiluanda) in the distance, the elders sent a toad to fetch tinder for fire. The toad bravely carried the tinder across the waters but collapsed before completing the journey, extinguishing the fire. Its back was scarred from the effort, which is why toads have bumpy skin today.

After several failed attempts, the elders turned to the birds for help, but it wasn’t until a bird called “kabis,” adorned with rainbow feathers, succeeded. It retrieved the fire, but a sudden gust of wind scorched its feathers black, while its beak and claws burned red. This is the origin of the black bulbul, a sacred symbol of bravery for the Bunun people. “If you spot a black bulbul, consider yourself lucky,” says Laung.

And how did the story end? To stop the flood, a giant crab emerged to confront the python. The crab’s hard shell withstood the python’s bite, leaving two marks on its shell that are still visible today. Eventually, the python was cut in two, releasing the waters and shaping Taiwan’s mountains and valleys. To this day, the Bunun people revere the toad and the black bulbul, teaching that they must never be harmed, while Yushan remains their sacred mountain.

This scene depicts how, according to Bunun folklore, the toad helped the ancestors survive by carrying tinder across the waters to them.

This final scene depicts the Bunun ancestors receiving tinder from the red-billed black bulbul, now revered as a symbol of bravery in Bunun culture.

Residing in Taiwan’s high mountains, the Bunun people rely on farming and hunting. Central to their seasonal ceremonies is millet cultivation, starting with the clearing of dry fields and sowing of millet, and concluding with a series of celebrations after the harvest. Each month’s rituals are aligned with the phases of the moon. Given that millet is the foundation of their livelihood, it remains deeply embedded in their culture, shaping their rituals, customs, and taboos.

To mark these rituals throughout the year, the Bunun people have created a unique ritual calendar known as Islulusan (or banli in Mandarin, meaning “plate calendar”), written in their own primitive script. This makes the Bunun the only indigenous group in Taiwan with its own written language.

Laung explains the meanings behind the various symbols used by the Bunun people, guiding us in understanding how to read their ritual calendar, Islulusan.

In this cozy hut, nestled in the heart of the Langdun village, guests are invited to immerse themselves in the unique scents and flavours of the Bunun people.

The Scent: Discovering Maqav

After touring Tamazuan village, we were taken across the Zhuoshui River to Langdun Village, officially known as “Renhe Village” in Mandarin. While Tamazuan gave us a glimpse into Bunun history and culture, it is here in Langdun where new sensory experiences await.

Taiwan is home to a rich variety of unique plants, one of the most notable being an indigenous spice known to the Bunun people as “Maqav.” Also referred to as “wild pepper” by non-indigenous locals, this fragrant spice plays a significant role in the daily lives of Taiwan’s indigenous tribes.

Maqav is prized for its distinct aroma and is often used to enhance local dishes. When the Bunun go hunting, they carry rice balls seasoned with maqav as snacks and use maqav to marinate their catch in order to mask gamey flavours.

In recent years, as indigenous and tribal tourism has grown, maqav has gained popularity in the culinary world, notably in dishes like maqav chicken soup. The Atayal people also maximises the benefits of this plant by boiling its roots to treat headaches, while its fruits and leaves are consumed to alleviate fatigue.

For the Dan community, maqav has become an essential ingredient in perfumes, and we are invited to create our own signature scent. We’re guided by our instructor, Nabas, to select our top, middle, and base notes from a range of essential oils, mixing them in a 1:9 ratio with a base infused with the scents of fresh green maqav. This base is extracted to bring out maqav’s rich, complex aromas of lemon, lemongrass, and ginger, which at first strike me as unusual.

After the perfume is blended, we’re told to let it set for 24 hours before using it. When asked to put a label to my bottle, I name my creation “Uli.”

The instruments used to blend the maqav perfume are beautifully arranged on a Bunun-style tablecloth.

The Flavours: Exploring Bunun Cuisine

It’s about dinner time, and we’re all hungry. There’s no better way to experience life as a Bunun than by indulging in their cuisine to end the day.

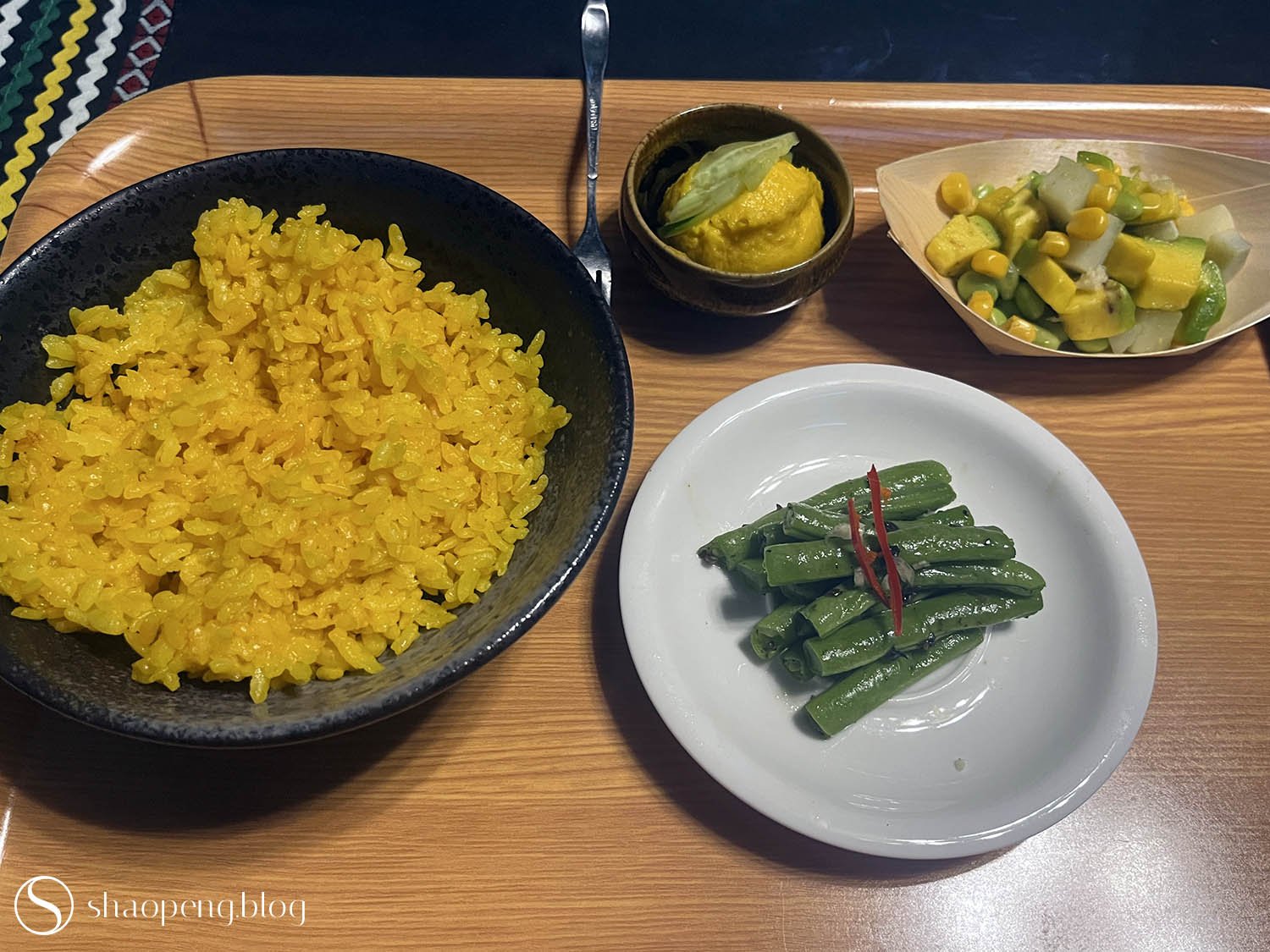

Each guest is first served a tray with a bowl of turmeric rice, accompanied by side dishes such as pumpkin mash, green beans seasoned with maqav, and a salad of diced avocado, potatoes, and corn, topped with a hunt of apple puree.

The highlight of the hot dish is the pumpkin shoots, the young leaves and tendrils of pumpkin vines. I particularly enjoy their unusual, fuzzy texture, which reminds me of “ice plant,” a popular vegetable choice for hotpot. According to our chef, Toubas, this dish is believed to be the first ever created by their ancestors.

Next, we try sugarcane tips from Puli. Similar in shape and flavour to bamboo shoots, these tender tops of the red sugarcane stalk are carefully handpicked and offer a sweet, subtle aroma. It’s my first time trying them, and they’ve quickly become one of my favourite dishes.

For the soup, pigeon pea — an ingredients considered indigenous to the Bunun — are used, enhanced with aged ginger and local herbs. For the main course, there’s the roast belly pork and fried capelin. Since I’m a pescatarian, I only eat the capelin.

To finish, we enjoy a traditional dessert of grass jelly soaked in nutritious nut milk.

By the time we finish dinner, night has already fallen, and the absence of light evokes reflection. It strikes me that there’s so much more to discover about Bunun people and their culture — this half-day trip is just a glimpse to their rich heritage, one that strives to glimmer in the dark but is often overshadowed by a world that favours globalisation over tribes, and international trends over local culture.

The Bunun, like the other 15 indigenous tribes in Taiwan, remain a minority. While the promotion of indigenous tourism has gained momentum in recent years, spending a day or two in the mountains shouldn’t be seen as a mere getaway from the concrete jungle. It should be an intentional journey to understand — and thus help preserve — their culture.

At the end of the day, I ask Laung if he feels enough work has been done to preserve their culture. He admits that they’ve been trying, but the truth is, much has been lost. Compared to the Atayal, who live in the nearby mountains and have artefacts dating back more than a hundred years, the Bunun have nothing of that sort.

I also ask where the Bunun textiles are, as weaving has always been at the core of indigenous tradition. “We’re re-learning it,” replies Laung. “Even the younger generation can no longer speak our language,” says Laung, his voice carrying a sense of helplessness.

Leaving the Bunun village with a heavy heart, I press on with my journey, holding onto the hope that by documenting the stories shard with me, their culture and traditions live on.

Tips for wanderer — For those planning to visit the Danda Bunun community, tours organised by the Danda Bunun Ecotourism Association can be booked via their website. To have a taste of the delicious Bunun cuisine, you can book your table at Wa Wa Gu Snack Bar.