Diving into the Deep Sea and Wander Through “Luminaries”

Luminaries: Annie Hsiao-Wen Wang’s Solo Exhibition recreates a unique oceanscape that will surely leave its visitors in awe.

TAIPEI, Taiwan — If you’ve ever walked into an art gallery, it was probably a “white cube gallery” where its unadorned white walls and lighting from above that set the backdrop for the works of art on display. The obsession with this aesthetic approach — introduced in the early 20th century in response to the increasing abstraction of modern art — does help to minimise distraction when reading the art.

As someone who’s accustomed to seeing art in a white cube, I was completely overwhelmed when I first stepped into Luminaries: Annie Hsiao-Wen Wang’s Solo Exhibition at the Yesart Gallery in Taipei city.

It was in broad daylight when I pushed the door open to enter the gallery, only to find myself lost in the dark. It was as if I’ve left the real world behind me, entering into this other dimension — or a parallel universe — that is very different from the world I used to know.

The sound of silence grows stronger in the dark, until I notice that there are sounds of deep underwater, coupled with those made by whales, playing in the background, giving me the illusion that I’m underwater.

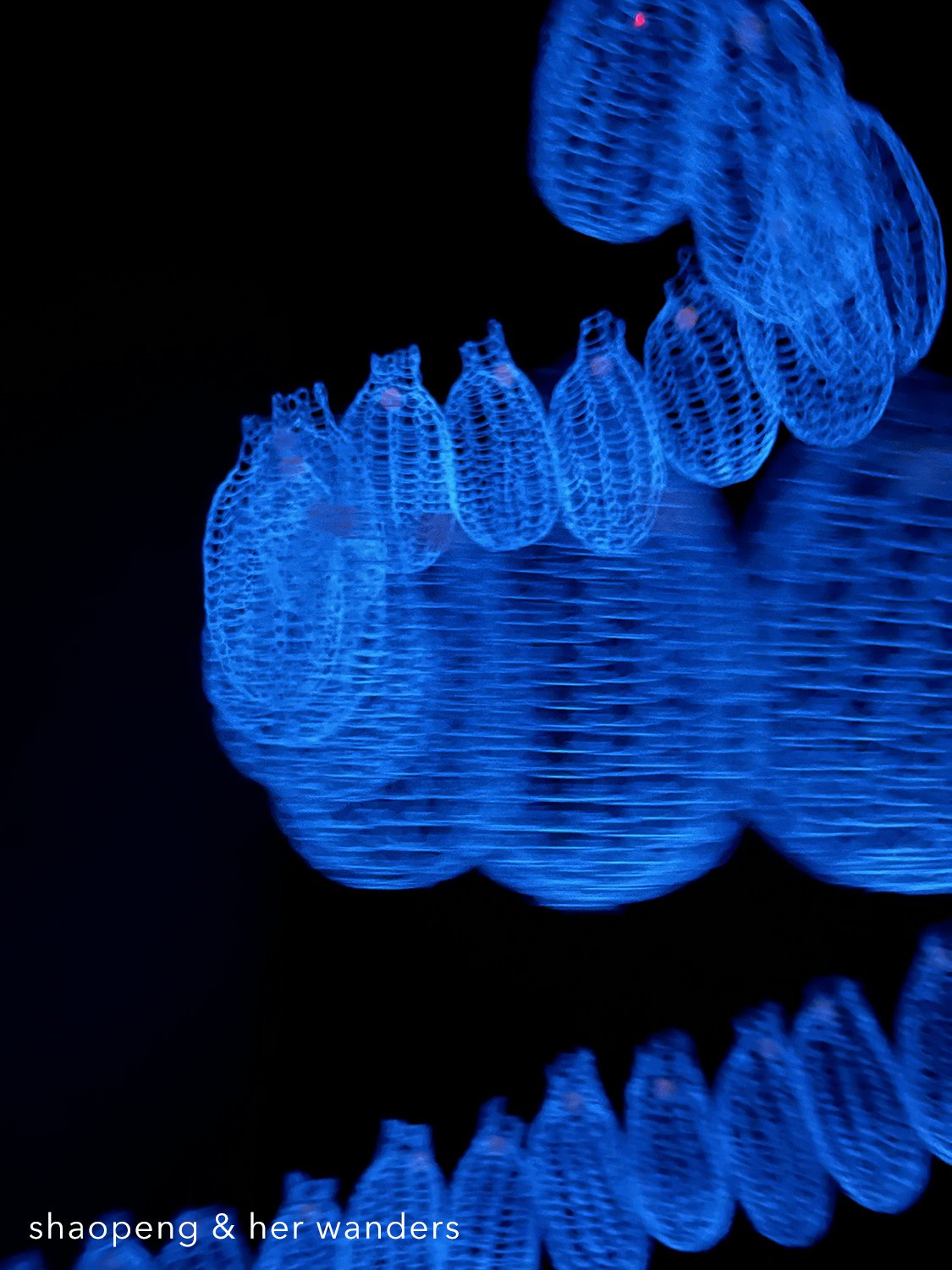

“Bubble Coral” close-up

As my eyes slowly adapt to the dark, my attention is immediately drawn to what looks like the glowing creatures that illuminate the darkest part of the ocean. I wander around the space like an experienced diver exploring the ocean’s deepest depths, not knowing what awaits me.

Luminaries is an exhibition that took Annie Hsiao-Wen Wang four years to prepare. Inspired by her love for marine life, particularly her infatuation with bioluminescent creatures in the deep sea, Wang recreated these living organisms in sculptures woven out of copper wire. The wires have been coated with fluorescent colour pigments, allowing these airy sculptures to illuminate the pitch-black gallery space the same way that marine creatures glow in the deep sea.

At the entrance is Bubble Coral, which emits a greenish-blue, almost turquoise, colour. Often mistaken as plants, corals are sessile animals with plant-like cells living in their tissues. By using a special wiring construction, Wang succeeded in transforming Bubble Coral into something that’s extremely light and delicate, sitting there on the pedestal like a beacon of hope.

Inside the exhibition Luminaries

Right across from Bubble Coral is a gigantic installation, Hydrozoa, a class of extremely small, predatory animals that look like jellyfish or plants. The artist has made their minuscule tentacles — known to be armed with stinging cells — to resemble those of an octopus. A fluorescent green glow emanates from Hydrozoa as it rotates clockwise, allowing visitors to examine this curious creature from all angles, even from below.

A total of nine works are on display. In this fascinating world, visitors will stumble upon a variety of marine species, such as, Sea Angel, Medusa, Comb Jelly, as well as Dumpling Squid. The way that these creatures hang in the space also gives them a poetic quality, very much like the innocent mobiles created by American sculptor Alexander Calder (1898–1976).

I’m particularly drawn to one of two comb jelly sculptures on display, which has been inspired by this bioluminescent creature that comes in all shapes and sizes. Characterised by its inverted tulip-shaped body, Comb Jelly 2 consists of three layers, each emitting a different colour: light blue, blue to purple from inside out.

Comb Jelly 2 inside the exhibition Luminaries

A closer look at the wire construction reveals that a random selection of colours in red, orange, green colour has been applied along the edges, as if mimicking the pulsating stripes of rainbow colours displayed by comb jelly. The wirework, together with the application of fluorescent pigment, not only brings out the transparency and gelatinous quality of this living organism, but has magically transformed the rigidity of metal wire into something that’s extremely light and delicate.

Up on the ceiling is Dragonfish — the longest work on display — that measures 360 metres in length. Found 2,000 metres in the ocean, black dragonfish is a long slender fish that’s known to emit extremely dangerous poison. The wire construction, coated in a gradation of colour from turquoise to blue, mimics how the creature’s body would shimmer for the purpose of predation.

Salp Colony caught in motion

Sitting in the far end of the room is Salp Colony. Salps are semi-transparent zooplankton that ranges in size from a few millimetres at birth to around ten centimetres as they grow (except for one species).

Salp glides through the water to link with their fellow salps in colonies, forming beautiful spirals or shapes in the ocean. On display, Salp Colony rotates in extremely slow motion; its spiral design and gigantic size compete for visitor’s attention amongst other bioluminescent creature living in this mesmerising oceanscape.

By transforming the tiniest — some even microscopic — deep-sea organism to large-scale sculpture, Wang hopes to increase people’s awareness in protecting the marine ecosystem. Therefore, 10% of the proceeds from the exhibition will be donated to Mission Blue, an organisation led by legendary oceanographer Dr. Sylvia Earle, in the hope of inspiring action to explore and protect the ocean.

It’s only afterwards — after I’ve returned to the ocean surface — when I realise that I’ve stayed underwater for more than an hour’s time. The fact that the perception of time can be altered when one wanders through this enchanting world of Luminaries leaves me in awe.

The exhibition Luminaries: Annie Hsiao-Wen Wang’s Solo Exhibition is now on view at Yesart Gallery, Taipei city, and runs through August 24th, 2022. To learn more about this exhibition, visit here.