Wander in Palermo: Cappella Palatina

Stepping into the Cappella Palatina, I was met by geometry, gold, and God — where Norman ambition, Byzantine splendour, and Islamic artistry mingle under one roof.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

A masterpiece of cultural fusion, the Cappella Palatina in Palermo is a treasure trove of Norman, Byzantine, and Islamic influences.

PALERMO, Sicily — It’s an early Tuesday morning. I arrive at the Palazzo dei Normanni (Royal Palace). As soon as I step inside, I instinctively search for the way to the Cappella Palatina (Palatine Chapel), only to find a queue of visitors already forming, some waiting impatiently.

The chapel’s fame is undeniable. Sharing a UNESCO World Heritage designation with the Royal Palace under the evocative title “Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale,” Cappella Palatina is often hailed as the crown jewel among the nine listed monuments (see Wander in Sicily: In the Footsteps of the Arabs).

I’ve been longing to visit this chapel ever since it appeared in my Islamic art history syllabus a decade ago. Back then, it glistened in my imagination as an emblem of Sicily — the part of Italy I missed while studying jewellery in Florence. And now, here I am: older, a bit more wise (my wishful thinking), but with the same wide-eyed excitement of a student.

They say dreams fulfilled often feel surreal. Standing outside what’s often likened to a jewel box of cross-cultural brilliance — the masterpiece of Norman King Roger II (reigned 1130-1154) — my heartbeat races. Excited? Undoubtedly. But also slightly anxious, as if I were about to meet someone I’ve admired from afar for too long.

While waiting, I take in the palace’s courtyard, named after the victory of Bernardino de Cardines, Duke of Maqueda, who had it built between 1598 and 1601. Above me, 19th-century mosaics quietly recount the life of Saint Peter and the tale of Absalom’s rebellion against King David. Created by Pietro Casamassima with remarkable finesse, they serve as a quiet prologue to the splendour that awaits behind the wall.

The wooden door to Cappella Palatina’s south aisle sits beneath another mosaic by Casamassima, this one depicting the Genius of Palermo offering a portrait of Ferdinand III (reigned 1759–1816) and his queen Maria Carolina — a fitting threshold to a world where history, religion, and art converge.

Guidebooks often say that Cappella Palatina is a blend of Norman, Byzantine, and Islamic cultures. But what does that actually look like? Let’s take a closer look.

While waiting to enter, visitors can admire 19th-century mosaics narrating St. Peter’s life.

Inside the Cappella Palatina, the view toward the presbytery reveals the full splendour of Byzantine mosaics.

Norman Ambitions Realised

The Normans first appeared in southern Italy in the early 11th century, replacing the Byzantines. Roger II strategically built his palace atop older Arab fortifications, securing his court from potential uprisings. The existing fortress did include a chapel, but Roger envisioned something far grander.

Commissioned in 1130, the Cappella Palatina emerged as a three-nave church crowned with a central dome — a place that embodied Roger’s expansive vision of a kingdom that spanned faiths, geographies, and cultures.

Though Byzantine in appearance at first glance, the chapel incorporates Islamic motifs in its wooden ceilings often referred to as muqarnas, as well as Greco-Roman columns and capitals. Its marble floor, patterned in the opus sectile technique, reflects the aesthetics and sensibilities of both Byzantine and Islamic traditions.

The Norman king enlisted a cosmopolitan team: Greek artisans for mosaics, craftsmen from Provence and Campania for sculpture, and carpenters and painters from Cairo for the ceilings.

The chapel functioned not only as a royal place of worship but also as a ceremonial hall. Arabic inscriptions on plaques liken the palace to the Kaaba in Mecca, encouraging guests to greet the king with rituals reminiscent of those performed during the Hajj. A grand marble throne on the western wall — situated beneath a radiant Christ Pantocrator — symbolises the king’s divine right to rule, mirroring the heavenly sovereign above.

All in all, the Cappella Palatina was a locus of power, where the Norman king displayed not only his military might but also the geographic and cultural position of his realm — poised between East and West, Islam and Christianity — worlds whose languages, artistic forms, and traditions he claimed mastery over.

The opus sectile inscriptions from the Cappella Palatina — now on display at the Palazzo Abatellis (Regional Gallery of Sicily) — liken the Norman palace to Islam’s most sacred site, the Kaaba in Mecca.

Byzantine Splendour in Gold

The moment you step inside, it hits you: gold, everywhere. The walls, arches, and dome shimmer with tesserae mosaics that dazzle the eyes and overwhelm the senses. These 12th-century mosaics recount the Genesis story — from the creation of light to the formation of sun, moon, stars, beasts, and humankind.

Mosaics, a hallmark of Byzantine artistry, were typically reserved for domes and apses. But here, they sprawl across every surface like illuminated manuscripts in stone and glass, substituting brushstrokes with tesserae to create vivid frescoes in gold.

Scenes from the Genesis cycle, such as the creation of heaven, Earth, and light (top left) and Noah’s ark (bottom right), are beautifully rendered in gold mosaics.

In the south transept, a scene shows John the Baptist, clad in a camel-hair tunic, baptising Jesus by placing his hand on his head and immersing him in the waters of the Jordan.

A majestic Christ Pantocrator presides over the chapel’s western wall, flanked by Saints Peter and Paul and watched over by archangels Michael and Gabriel. They all stand against a backdrop of shimmering gold. Oscar Wilde once wrote:

“The Cappella Palatina, which from pavement to domed ceiling is all gold: one really feels as if one was sitting in the heart of a great honeycomb looking at angels singing.”

Turn toward the north, and you’ll see the presbytery — the part of the chapel most often featured in guidebooks. Somehow, this niche-like space reminds me of the mihrab in a mosque.

Here, Christ Pantocrator reappears above the Annunciation scene. Rendered in exquisite detail, he is seen wearing a blue cloak over what might be interpreted as shimmering silk. He holds an open book that reads, in Greek and Latin: “I am the Light of the world…”

Looking west inside the Cappella Palatina, Christ Pantocrator is shown enthroned, flanked by Saint Peter (left) and Saint Paul (right).

While admiring the Byzantine mosaics, one can’t help but notice the richly painted wooden ceiling above the central nave.

Echoes of Arab Artistry

And then, there’s the ceiling. Oh, the ceiling.

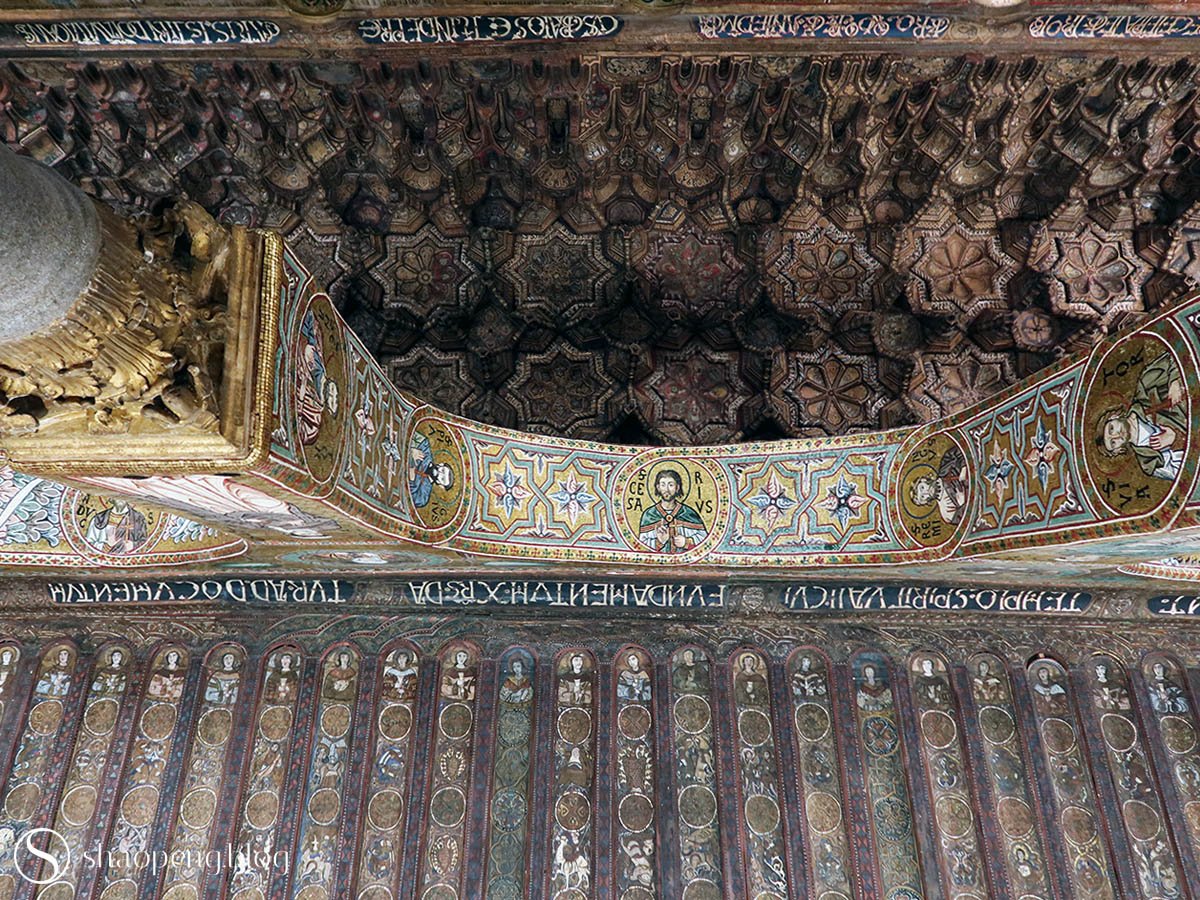

Fate has it that the chapel’s most original and remarkable feature is also the one least visible to most visitors. The painted wooden ceiling soaring over the central nave is unlike anything else in the world. It’s in essence a geometric dance of muqarnas — that iconic honeycombed stalactite structure so beloved in Islamic architecture (for more on this, see Wander in Palermo: Castello della Zisa).

But what truly sets this ceiling apart is its unique craftsmanship — the Cappella Palatina houses the only known muqarnas crafted from thin wooden panels instead of stucco or carved wood. Created in the early 12th century, this honeycombed ceiling sets the stage for courtly fantasies.

Camels carry lovers, dancers perform, musicians play square drums. The most recurring character is the nadim, or royal drinking companion, often shown in the middle of drinking. My personal favourite is a pair of men playing chess — the oldest known depiction of the game in Europe. Here, chess is more than a pastime; it’s an essential part of a nadim’s duties.

The wooden ceiling of the central nave stands as the oldest surviving structure of the Cappella Palatina.

The world’s oldest known depiction of chess game is hidden amidst the kaleidoscopic decoration of the chapel’s muqarnas ceiling.

The wooden ceiling above the aisle is richly adorned with figures, animals, and intricate patterns.

Arabic inscriptions border eight-pointed stars, praying for divine favour on the king. Some are legible; others are rendered in pseudo-script. To truly appreciate them, bring a zoom lens or invest in a guidebook—the chapel’s ceiling deserves more than a passing glance.

While the Royal Palace lost its political prominence under the Hohenstaufen and later Spanish rulers, and while much of its Norman architecture has faded or been built over, the Cappella Palatina has survived nearly unaltered. It is a capsule of time — a golden sanctuary that has held its ground for nearly a millennium.

By the time I finally — albeit somewhat unwillingly — step out of the chapel, the crowds have thickened, but somehow, my heart feels lighter.

For a wanderer at heart, the Cappella Palatina is not just a destination; it’s a place where the heights of an empire speak not through conquest, but through mosaic, marble, and muqarnas. And for those who listen closely, the chapel offers more than beauty for the eyes; it offers a sense of belonging — however fleeting — in a world once imagined whole.

The royal throne is beautifully adorned with mosaic work that celebrates geometry and symmetry, reflecting both Byzantine and Islamic influences.

Reference:

Johns, J. (2015). Arabic inscriptions in the Cappella Palatina: Performativity, audience, legibility and illegibility. In A. Eastmond (Ed.), Viewing inscriptions in the late antique and medieval Mediterranean (pp. 124–147). Cambridge University Press.

Vicenzi, A. (Ed.). (2011). La Cappella Palatina a Palermo [The Palatine Chapel in Palermo]. Franco Cosimo Panini Editore Spa.