Recipes for Broken Hearts: A Wanderer’s Take on Bukhara Biennale

At the Bukhara Biennale, visitors set out on a caravan’s journey through this ancient Silk Road city, where more than 70 site-specific works of art offer their own recipes for mending broken hearts.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★★

Davlat Toshev’s Haft Avrang (“Seven Colours of Heaven”) employs Abru-Bahor (ebru), the art of marbling paper believed to have originated in Bukhara.

BUKHARA, Uzbekistan — A year ago, I wouldn’t have imagined returning to Uzbekistan exactly one year after my first visit. Back then, I held onto the wishful thought of attending the inaugural Bukhara Biennale. I assumed that wish had long faded until it resurfaced at the right moment, with the right companions, turning this dream getaway to a reality.

For centuries, Bukhara has been shaped by the ebb and flow of people, ideas, and cultures. The polymath Al-Biruni (973–1050) once called it “the meeting place of the learned, the sanctuary of wisdom, and the cradle of civilisation.” As a vital hub along the ancient Silk Road, it’s inevitable that Bukhara would become the stage for Uzbekistan’s first international art biennale.

Commissioned by Gayane Umerova and envisioned by Artistic Director Diana Campbell, the biennale opened in early September with more than 70 site-specific works — all newly commissioned by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation — dispersed across the city’s historic quarters.

Its title, Recipes for Broken Hearts, caught me off guard at first. I later discovered it drew inspiration from the celebrated physician and philosopher Ibn Sina (circa 980-1037) who is said to have invented palov — now Uzbekistan’s national dish — to mend the broken heart of a young prince forbidden to marry the daughter of a craftsman.

For the general public, the Bukhara Biennale is a feast for the senses that casts this millennia-old city in a new light. For art lovers, it offers something rarer: encounters that resist today’s highly commercialised art world. By bringing together emerging artists and Bukhara’s master artisans from various disciplines, each work becomes a true co-creation — art that listens, converses, and belongs to the city’s living heritage.

Prior to my trip, little about the event could be found online besides the official website. A handful of articles appeared after the opening, but most only skimmed the surface. This is why I wanted to share my own journey here — both as a guide for fellow wanderers (so you know what to expect and what not to miss) and as a window for those who are unable to attend in person.

To wander the Bukhara Biennale is to join a caravan. At each stop, you’re invited not only to meet the artworks but also to reflect on the histories, memories, and traditions layered into the very sites that hold them:

Magoki Attori Mosque

Inside the 12th-century Magoki Attori Mosque is an intimate exhibition, The Bukhara Archive, where the voices of older generations recall the city’s collective memory, culture, and traditions.

The journey begins on Mehtar Anbar Street, transformed for the biennale into both an information point and a mini bazaar. Just a short walk from here, you arrive at the first stop: the Magoki Attori Mosque.

Dating back to the 12th century, Magoki Attori is the oldest mosque in Bukhara. Its foundations lies an even deeper story — it was built on the site of a Zoroastrian temple, and in one corner you can still find traces of the furnace once used for fire worship.

Originally home to the Carpet Museum, the mosque now hosts The Bukhara Archive, curated by the Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF). Though not officially listed as the biennale’s starting point, it feels like the most fitting one: a place where Bukhara’s history and memory are given voice.

In this multimedia exhibition, you’ll encounter artisans, teachers, scholars, chefs, and spiritual leaders — guardians of knowledge and tradition who keep the city’s legacy alive.

I’m especially drawn to the interview with Jumayev Baxshullo, a master of gold embroidery, who speaks of Bukhara’s golden age as a city of crafts. Can you imagine that more than 200 trades once thrived here? I later cross paths with him at his shop near Toqi Zargaron, where we share a brief but heartfelt exchange.

The culture of a city lives not only in its monuments, but also in the stories carried by its people. Oral histories, like those gathered at the Magoki Attori Mosque, offer you a different lens to understand Bukhara’s rich heritage.

Wanderer’s tips — Set aside at least 40 minutes to watch all seven interviews. It’s worth it. By the end, you’ll see Bukhara with new eyes.

Toqi Sarrafon

Suspended from the ceiling of Toqi Sarrafon, Through Bloom and Decay is woven from isiriq, a plant native to Bukhara, honouring the special place it holds in Bukharian life.

As you wander the historic centre of Bukhara, the trading domes are hard to miss. Dating back to the 16th century, each of these covered bazaars was dedicated to a different trade. The Toqi Sarrafon, for instance, served as a centre for currency exchange run by Indian and Jewish money changers, known as sarraf.

Throughout the biennale, its vaulted ceiling is transformed by Munisa Kholkhujaeva’s chandelier-like installation Through Bloom and Decay. The piece was inspired by her visit to Chor-Bakr cemetery, where she noticed wild plants rising taller than the tombs. In collaboration with Anton Nozhenko, she translates that observation into a bold sculpture that now hovers above this crossroads of the old city.

Look closer, and you’ll see it is made from Peganum harmala (isiriq), a medicinal desert plant that remains essential to local life — sold in bazaars, used in healing, and burned in rituals to ward off the evil eye. Walking beneath it, I can almost sense the dryness of the plant in the air.

Before moving on, don’t miss the mosaic hidden behind a lattice niche: one of Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s Eight Lives. This particular piece depicts a pair of kidneys, created in collaboration with mosaic master Rauf Taxirov and inspired by the traditional healing recipes her grandmother passed down. Each of the seven mosaics —scattered across the biennale — is dedicated to a different organ, tying craft to the intimate knowledge of healing.

At night, Tower of Pomegranates glows with a presence that transforms its surrounding.

Along the Shakhrud Canal, the ancient artery of Bukhara’s waterways, an extended ikat tapestry urges reflections on the disappearance of the Aral Sea.

Step just outside the dome and you’ll find another work: Erika Verzutti’s Tower of Pomegranates, created with Bukharian woodcarver Shonazar Jumaev. A stack of carved pomegranates — symbols of fertility and abundance that are omnipresent in Uzbekistan — stands opposite a wooden column that has held up a structure for centuries. I find the dialogue between old and new subtle yet refreshing, especially at dusk, when the sculpture’s shadow stretches across the floor.

And don’t leave before taking a look at the Shakhrud Canal, once a lifeline that carried water from the Zarafshan River into the city. Suspended above it is Longing, an ultra-long ikat tapestry unfurling like an artery through the biennale’s route. Its colours shift gradually from deep blue into the arid shades of desert, a visual metaphor for the vanishing Aral Sea. Created by Hylozoic/Desires with the Margilan Crafts Development Centre, the work is both tender and unsettling, urging you to reflect on loss that is both ecological and emotional.

Wanderer’s tips — Keep your eyes open for artworks displayed in public spaces. Some blend so well with their surroundings that you might almost miss them!

Caravanserai

In collaboration with Bukharian mosaic master Bakhtiyar Babamuradov, Marina Perez Simão reimagines the courtyard of the Caravanserai with a ceramic tile floor inspired by the celestial.

For travelling merchants, Caravanserais were once places of rest as well as centres of commerce. One of the most intriguing venues for the Bukhara Biennale is the Caravanserai complex, made up of four interconnected carvanserais: Fathullajon, Ayozjon, Ahmadjon, and Mirzo Ulugbeg Tamakifurush.

Dating to the 18th and 19th centuries, this complex features a central courtyard, its floor now taken over by a giant mosaic imagined by Marina Perez Simão. In collaboration with Bukhari mosaic master Bakhtiyar Babamuradov, the Brazilian artist reimagines a celestial map inspired by the region’s astronomers and mathematicians who have gazed at the sky with wonder since ancient times.

Around the courtyard are small rooms called hujras, as well as stables for horses. Wandering through the interconnected hujras is like exploring the inner chambers of the heart. Near the entrance, you’ll discover another installation from Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s Eight Lives, depicting the heart. The mosaic sits against a backdrop of herbal plants that local women have long used to heal their loved ones.

On display at the Caravanserai, one of Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s Eight Lives depicts the heart, accompanied by traditional herbs used by Bukharian women to heal their loved ones.

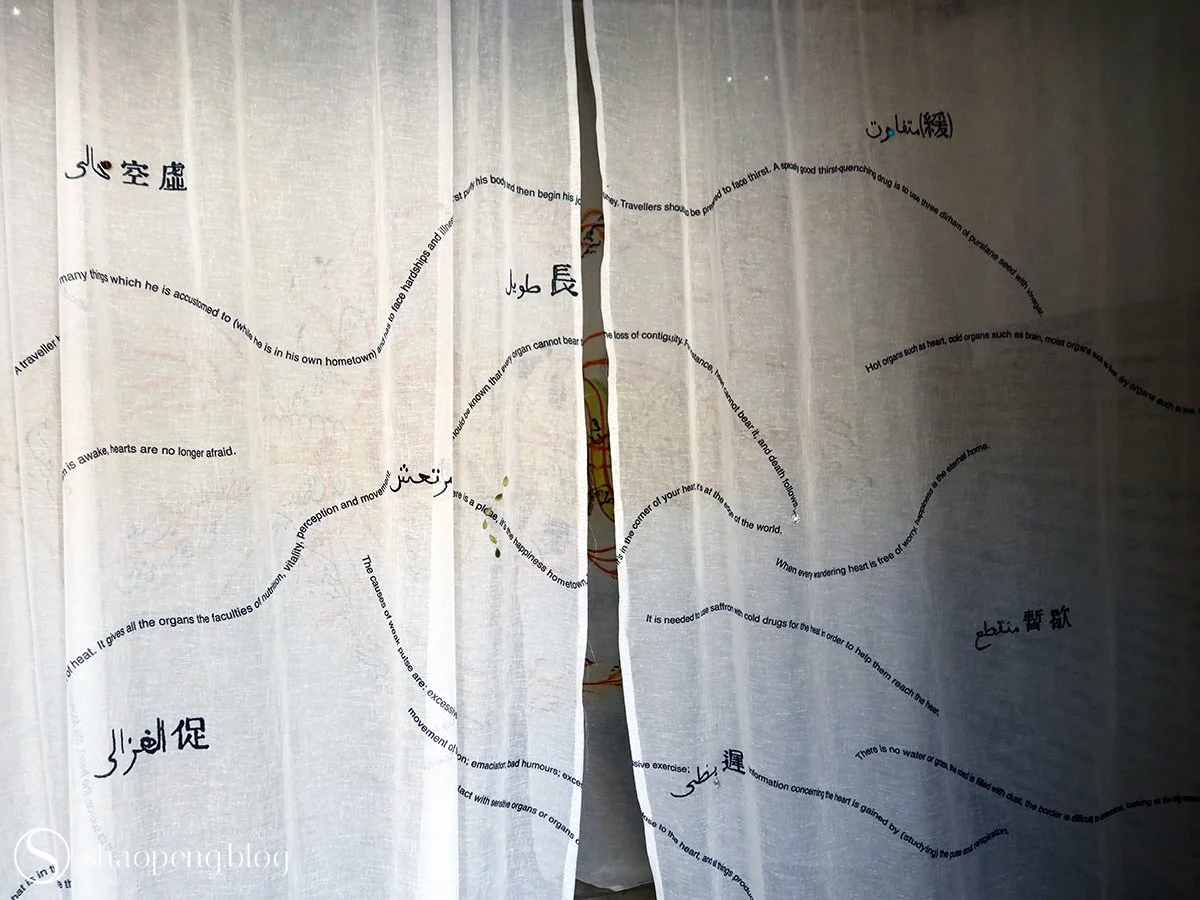

On layered silk curtains, words and phrases in English, Arabic, and Chinese are delicately embroidered, guiding visitors into Qu Chang’s Happiness Hometown.

Keep moving, and you’ll come to the rooms housing Chinese artist Qu Chang’s Happiness Hometown. Layers of silk, embroidered with texts in English, Arabic, and Chinese, trace the journeys of travellers who once sought refuge within these mud-brick walls. I find myself lingering in these rooms, fascinated by the delicate stitching and the gentle invitation to open one’s heart along the route to happiness.

Nearby, Anna Lubina’s Bukhara Peace Agency unfolds within a tent lined with traditional suzani embroidery and carpets, created in collaboration with local artisans. Inspired by the sozandas — female ritual leaders who combine Persian poetry, Zoroastrian symbols, and dance — the tent offers shade from the blazing sun and invites visitors to contribute their own recipes for peace, in words or drawings. I’m also drawn to Veera Rustomji’s Ossuaries for Bukhara, where ceramic ossuaries — paying homage to Zoroastrian customs once rooted in the city — are placed in niches originally used for feeding donkeys.

At the Caravanserai, Anna Lubina’s Bukhara Peace Agency is housed within a tent where visitors are invited to share their own recipes for peace amid a world of chaos.

Pakistani artist Veera Rustomji’s Ossuaries for Bukhara reflects on the Zoroastrian practice of placing the bones of the deceased in ossuaries, keeping body and earth apart.

It’s remarkable to see how the historic Caravanserai is transformed by the presence of artworks both indoors and outdoors. True to its original purpose as a meeting point for merchants and travellers from far-flung regions, the works on display are international — from South Korea, China, Mongolia, India, Pakistan, Jordan, Senegal, Egypt, and Morocco — turning the Caravanserai into a crossroads of creativity, where ideas spark curiosity and wonder among visitors.

Wandering through the space, I can’t help but wonder: could heartbreaks in our lives serve a greater purpose? Would it be possible that heartbreaks are never meant to defeat us, but instead open rooms for transformation and growth?

Wanderer’s tips — The Caravanserai is huge. Keep an eye out for staff wearing “Mediator” tags — they can guide you through the stories behind each work. You’ll be surprised at how much thought and care has gone into every creation.

Olimjon Caravanserai

In Kutadgu Bilig, Saule Suleimenova incorporates plastic bags collected from the people of Bukhara, making the city’s residents active contributors to the artwork.

Further along, you’ll pass by the discreet Olimjon Caravanserai, where an installation by Kazakh artist Saule Suleimenova is a wonder in itself. When viewed from afar, the work consists of seven canvases, each depicting men and women donned in Central Asian attire, caught in action of singing and dancing.

But look closer, and you’ll be surprised to find that each figure is meticulously crafted from polyethylene bags collected from the people of Bukhara. The transformation of these everyday, disposable items into something so intricate and expressive invites reflection on the value we assign to the mundane.

Throughout the biennale, this installation sets the stage for live performances by the Shiru Shakara folk ensemble — retired performers who celebrate the simple joys of daily life.

Titled Kutadgu Bilig, meaning “the wisdom that brings happiness,” the work offers yet another recipe for broken hearts: a gentle reminder that heartbreaks can be met with wisdom, and that happiness, ultimately, is a choice.

Wanderer’s tips — Visit around midday when the sun is at its highest, so the canvases’ colours and details shine at their fullest.

Gavkushon Madrasa

At the Bukhara Biennale, Navat Uy — a pavilion built from crystallised rock sugar — stands before Gavkushon Madrasa, once a slaughterhouse.

A few steps further, you arrive at the Gavkushon Madrasa. Built in 1570, the madrasa follows a traditional courtyard layout with over 30 rooms. Its name, Gavkushon, means “bull slaughter,” hinting at its former use as a slaughterhouse. Outside its entrance stands Navat Uy by Egyptian artist Laila Gohar.

This small pavilion — crafted entirely from the traditional Uzbek crystallised rock sugar known as navat — sparks wonder for both children and adults. More than a sweet treat, navat carries a long heritage as a symbol of hospitality and collective memory in Central Asia that predates industrial sugar. Considered a folk remedy for coughs and sore throats, navat’s presence here is both playful and meaningful - so much so that even wasps are drawn to its sweetness.

The Blue Room, a collaboration between ceramic artist Abdulvahid Bukhoriy and coppersmith Jurabek Siddikov, extends the spirit of the former prayer room within the Gavkushon Madrasa.

Inside the madrasa, the first room to your right is The Blue Room, once a prayer chamber. Uzbek ceramic artist Abdulvahid Bukhoriy transforms the space with handcrafted blue tiles, while a chandelier-like sculpture by coppersmith Jurabek Siddikov hangs above.

Submerged in this blue world, you feel shielded from the heat outside. The room’s quiet, meditative atmosphere invites reflection, while the blue glaze — extracted from a plant harvested during the biennale’s season — ties art to the rhythms of nature. Once inside, you can’t help but lower your voice, as if the spirit of the former prayer room has come alive.

Qourds & Qurban, revolves around the motif of melons, is the fruit of a collaboration between Slavs and Tatars and master potter Abdullo Narzullaev.

One of my favourite installations here is by Slavs and Tatars: 40 species of melons suspended against a backdrop of ceramic plates. In Central Asia, melons are considered divine gifts, their lines inscribed with sacred messages. The plates bear transliterations of over 40 melon varieties — from Cyrillic Karakalpak to Arabic script — based on a 1977 compendium. These calligraphic marvels are the work of master potter Abdullo Narzullaev from Gijduvan. It’s such a delight to see how everyday fruits are transformed into a meditation on culture and craft.

Two rooms are devoted to Davlat Toshev, who covered walls and ceilings in marbled paper using the Abru-Bahor (ebru), technique, said to have originated in Bukhara. Once used to frame miniature paintings, here it is reimagined on a monumental scale, accentuated by a few pomegranate trees depicted in the centre of the walls. The space feels sacred, not in a religious sense, but as a realm of imagination, art, and healing.

For Toshev, art itself is a medium of healing, evident in the school he founded for deaf and mute individuals, where painting becomes a voice. I wonder: perhaps the recipe for mending broken hearts lies not just in the artworks, but in the process of creating and experiencing them.

Here, you’ll also find Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s mosaic depicting a pair of lungs. Placed near the four mulberry trees in the courtyard, the work of art seems to breathe in the oxygen these trees provide, allowing the lungs to bloom with flowers.

Wanderer’s tips — Davlat Toshev’s home studio (location) is just a stone’s throw from Gavkushon Madrasa. Be sure to visit to explore the artist’s world more deeply.

Khoja Kalon Mosque

The courtyard of the Khoja Kalon Mosque is transformed by installation works from Delcy Morelos and Antony Gormley.

Next, you arrive at the Khoja Kalon Mosque, part of the Khoja Gavkushon ensemble. Built in 1598, it’s the second-largest mosque in Bukhara, though much of the structure collapsed in the past century and was repurposed as a warehouse, leaving only the minaret standing.

On its façade, you’ll notice traces of “textile repairs” reimagined by artist Hana Miletić. These delicate interventions pay homage to the often-overlooked patches improvised by local residents on cracked walls. In collaboration with master gold embroiderers from Bukhara, Miletić brings the act of repair and healing to the forefront, turning unnoticed gestures into visible art.

Step inside, and a giant golden pyramid by Colombian artist Delcy Morelos captures your attention. Interwoven with jute threads using the “Eye of God” technique, the work fuses Uzbek textile traditions with indigenous practices from the Americas. While wandering around the pyramid, you’ll catch a scent in the air: desert sand with cloves, cinnamon, and turmeric, carefully composed by a fourth-generation Bukharian spice merchant.

The remainder of the courtyard is taken over by Antony Gormley’s labyrinth of mud bricks, made in collaboration with Bukharian restorer Temur Jumaev. At first glance, it feels like you’ve stepped into a cemetery. Look closer, and each brick reveals itself as a pixelated figure, frozen in a variety of poses — some sitting, some reclining. According to Gormley, the labyrinth celebrates the mudbrick, a technique honed over thousands of years and still alive in Bukhara today.

It’s remarkable to see how this historic site — currently undergoing restoration — has been transformed through art. Perhaps the lessons for a broken heart are similar: healing comes in two ways, by mending visible scars, like those on the building’s façade, and by tending to the inner self.

Wanderer’s tips — Visit before sunset to see the pyramid by Hana Miletić bathed in golden light. Outside, don’t miss Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s mosaic of the brain.

Oshqozon Café

Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s “stomach” mosaic finds a fitting home in the Oshqozon Café.

What better way to experience the biennale than through taste? Just across from the Khoja Kalon Mosque is the Oshqozon Café, where visitors are treated not only to traditional Uzbek dishes but also to a curated experience of culinary art.

“Oshqozon” means “stomach” in Uzbek, and above the entrance, you’ll spot Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s mosaic of a stomach. The word can also be read as “vessel to prepare food” — a fitting symbol for a space where nourishment and creativity meet.

I’m fortunate to attend the first session of the Chef’s Programme, a special menu prepared by Saidakmal Vahobov and the Qand Team. Every dish revolves around sweet flavours and the chefs’ personal memories, adapted into traditional Uzbek cuisine.

If remedies for broken hearts sometimes fall short, food rarely does. As Diana Campbell puts it, this is “a joyful world where everyone’s heart can feel lighter and everyone’s stomach can be full.”

If you think the remedies for broken hearts may not heal you, food certainly can. In Diana Campbell’s words, “a joyful world where everyone’s heart can feel lighter and everyone’s stomach can be full.”

Wanderer’s tips — Check the biennale’s official website to book a spot at the Chef’s Programme; it’s a sensory experience not to be missed.

Rashid Madrasa

Home of Hope by Jenia Kim revives the migratory birds — once a symbol of Bukhara but lost during a water crisis — through a collaboration with Bukharian blacksmiths, opening a dialogue on culture from the perspective of the Korean diaspora.

Walking along the Shakhrud Canal, you arrive at Rashid Madrasa — the official final stop on this journey to mend broken hearts. You’ll likely be struck by the building’s unexpected look: its façade fully draped in coloured ikat, evoking a life-sized Barbie house. In fact, this area once served as a neighbourhood of embroiderers.

The installation is the work of Kazakh artist Gulnur Mukazhanova, who was inspired by a myth about the origin of Uzbek ikat fabrics. Legend has it that the first ikat pattern was born from an artisan’s tear drop falling on water, its ripples creating a rainbow across the surface. In collaboration with the Margilan Crafts Development Centre, Mukazhanova has transformed the entire façade into a textile portal — an unusual yet fitting remedy for heartache.

Step inside, and you might find yourself smiling at the sarcastic, playful installation by Qatari artist Majid Al-Remaihi, which reimagines the tales of Khoja Nasreddin through the streets of Bukhara in 2025. Nearby, Uzbek artist Jenia Kim pays homage to her Korean heritage, weaving personal and cultural narratives into the space.

Upstairs, you’ll come across a curious installation titled Black Bile by Lithuanian artist Pakui Hardware. Strange ear-like instruments invite you to speak into them, confiding a heartbreak — or a memory — you can’t let go of. The installation brings to mind Ibn Sina’s belief in the healing power of active listening: the stories you whisper are transformed by an algorithm into musical compositions, later played at the Caravanserai.

As I try telling a story of heartbreak from my past, I feel the weight lift. Though I’m not sure if I’ll ever be fully healed, what matters most is that I haven’t come this far alone; close friends and loved ones are beside me at every step.

Perhaps this is why “liver,” the final piece of Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s Eight Lives, finds its home here. The liver cleanses the body of toxins, and in Uzbekistan, “jigar” is a term for close friends — those we can’t live without. Oyjon’s mosaic is easy to miss, tucked inside what appears to be an empty room, waiting for those who seek it.

Wanderer’s tips — When you finish here, cross the street and have a look inside the biennale’s pop-up library.

Al Musalla

Al Musalla, a mobile space for prayer, is thoughtfully positioned near the Kaylan Mosque, the heart of faith in old Bukhara.

Having seen Al Musalla in Jeddah earlier this year, I’m genuinely surprised to see it again here in Bukhara — I mean, what are the chances?

A musalla is, by definition, a space for prayer and contemplation. What makes this one special is that it lives beyond any single biennale. Its design allows it to be disassembled and reassembled with ease, evoking the movement of space that mirrors the journeys of caravans through time. A winning work of the Al Musalla Prize, launched by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation, it first premiered at the Islamic Arts Biennale 2025 in Jeddah. Seeing it placed next to the Kaylan Mosque adds a layer of meaning that makes it feel truly at home.

While sitting inside Al Musalla, I can’t help but reflect on my journey throughout the biennale. I arrived here with curiosity, eager to see what artists from Uzbekistan and Central Asia are creating. But to my surprise, it offers far more than what I could’ve imagined.

Learning the stories behind each work and understanding why it is placed where it is, completely transforms the experience. As a frequent visitor to art exhibitions and biennales, I can say that the Bukhara Biennale provides some of the most meaningful encounters I’ve ever had with contemporary art — art that is not made for the sake of art alone, but to celebrate heritage, collaborate with local artisans, and awaken memories of historic sites that might otherwise have been forgotten. No other contemporary art exhibition I know of taps so deeply into a city’s cultural legacy, now being reimagined by Uzbek artists and those from around the world.

Wandering through the biennale, you may or may not find a remedy that speaks to you personally, but each work invites introspection. Perhaps the true remedy for any form of illness — heartbreaks included — doesn’t come from the outside, but from within. The real question, then, is whether we’re willing to let go of our heartbreaks and the pain that comes with them.

Some might say it’s impossible to repair what’s broken, and that’s completely valid. But during my time in Bukhara, the people I encounter — young and old, from all walks of life — show me a kindness and generosity that opens my heart in ways I hadn’t anticipated. That, I would say, is the recipe I’ve found for healing.

On the surface, Recipes for Broken Hearts offers a remedy for personal heartbreaks. At a deeper level, it speaks to the wounds and fractures of cities or cultures on the verge of losing their traditions. The Bukhara Biennale is a celebration of continuity — a living blueprint illustrating how what is lost can be healed, revived, and reimagined through acts of creation, collaboration, and transformation.

*I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to Madinabonu Kayimova, a mediator at the Bukhara Biennale, for her dedicated and insightful tours on multiple occasions.

The Bukhara Biennale runs until November 20, 2025.