Wander in Bukhara: An Arts & Culture Guide

With over 2,500 years of history, Bukhara feels suspended in time — a place where the memory of the Silk Road still lingers, inviting you to wander through this crossroads of ancient worlds, a city whose very name carries the meaning of “God’s Joy.”

Sense of Wander: ★★★★★

Toqi Zargaron, one of Bukhara’s earliest trading domes, once housed dozens of jewellers’ workshops.

BUKHARA, Uzbekistan — With over 2,500 years of history etched into its ancient walls and cobbled lanes, Bukhara feels suspended in time. The facades of its madrasas invite stillness and reflection; its caravanserais stir memories of travellers who once crossed mountains and deserts; and its silks, ceramics, and embroidery shimmer like fragments of a shared dream.

The heart of Bukhara tells stories of empires that rose and fell, and of caravans that paused here along the ancient Silk Road. Situated at the crossroads of cultures, Bukhara became more than a trading hub — it was a meeting place of ideas, beliefs, and traditions.

Following the Arab conquest, Bukhara blossomed into a centre of learning and enlightenment. Within the walls of its mosques, madrasas, and libraries, knowledge was not only safeguarded but shared, making the city a beacon of wisdom. It was here that scholars, poets, and scientists shaped the course of thought — among them the physician and philosopher Ibn Sina (circa 980–1037), whose influence spanned medicine, philosophy, and even culinary arts, inspiring the curatorial theme of the Bukhara Biennale inaugurated this September.

Persian, Turkic, Mongol, and Arab legacies are not only preserved in manuscripts and monuments but woven into the rhythms of people’s everyday life: in the call to prayer from centuries-old minaret, the steady hands of artisans at work in their humble workshops, and the hot, puffy samsa pulled fresh from the tandir oven.

The origins of its name have been debated by historians, but I’m most drawn to Bukh Oro — “God’s Joy” in Sogdian — a name that still rings true in the warmth of its people’s smiles. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993, Bukhara offers more than history; it offers a way of being, a remedy to the haste and demands of modern city life. Here, I share my arts and culture guide to this remarkable city — one I hope you won’t miss when you visit Uzbekistan.

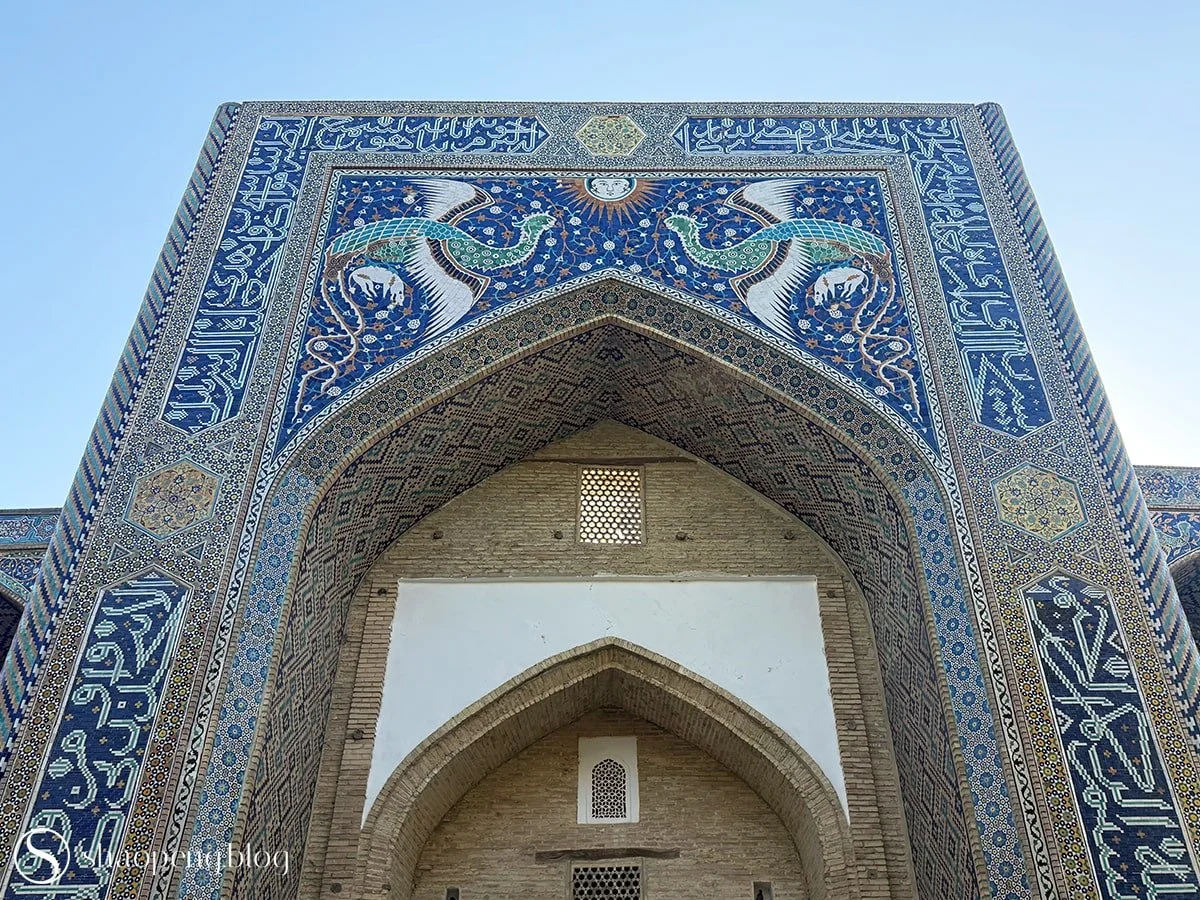

Nadir Devanbegi Madrasa

Sense of Wander: ★★★☆☆

A pair of huma birds hovers between myth and reality on the portal of Nadir Divanbegi Madrasa in Bukhara.

At the heart of Bukhara lies Lyabi-Hauz (“by the pool” in Persian) — an ensemble dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries. The pool at its centre is embraced on three sides by historic buildings: Kukeldash Madrasa to the north, Nadir Divanbeghi Khanaka to the west, and Nadir Divanbegi Madrasa to the east. In front of the latter stands the whimsical statue of Khodja Nasreddin riding his donkey — a favourite photography spot for many visitors.

Originally commissioned as a caravanserai by Nadir Divanbegi, vizier to Imam Quli Khan (reigned 1611–1642), the building was converted into a madrasa after the ruler of the Bukhara Khanate declared it was built in the glory of Allah. The vizier added a loggia, a portal, and a second floor for living quarters, though the structure lacks a typical madrasa porch, mosque, or large classrooms.

Nadir Divanbegi Madrasa captures the attention of most visitors, more so than its adjacent Kukeldash Madrasa, the oldest of the three. Passersby are naturally drawn to the intricate designs near the top of its portal, where mosaics depict a pair of mythical huma birds in search of a groom. Modeled after the Sherdor Madrasa in Samarkand, it replaces the sun-faced lions with these birds of happiness, lending the madrasa a unique charm.

Today, the rooms surrounding the madrasa’s central courtyard bustle with artisans at work — in woodcarving, metalworking, and embroidery. Here, visitors can witness crafts passed down through generations, and perhaps take home a piece of Bukhara’s artistry.

Wanderer’s tips — A folk performance of music and dance takes place daily at 18:00. Walk in freely or book a table in advance, as most spots are reserved for large tour groups.

The Puppet Museum

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

Inside the Puppet Museum in Bukhara is an array of puppets crafted by the workshop.

Did you know that Uzbekistan has a rich history of puppetry? I didn’t — not until I visited the Puppet Museum in Bukhara.

Puppet theatre in the region evolved from the earlier Masqara Theatre, a form of folk dance using zoomorphic masks that first appeared in the 4th century BC. By the 5th century, the art of puppetry, known as kugirchok uini (“play with puppets”), had emerged. The puppeteer, or kugirchokchi, brought these small figures to life with remarkable skill and imagination.

The Puppet Museum in Bukhara was founded by master puppeteer Iskandar Khakimov, who continues to produce puppets in his workshop upstairs. The process of crafting a puppet is complex: molding the plaster body, layering it with papier-mâché, painting faces, sewing costumes, and adding jewellery. Traditionally, men sculpt the figures while women handle the clothing and adornments.

In the early 20th century, Bukhara’s Darvozai Uglon quarter was home to around 40 families, including musicians and puppeteers. Today, only three families continue the craft, preserving a tradition that also thrives in Samarkand, Khiva, and Tashkent. Farrukh, a puppet maker with 13 years of experience, explained that Bukharan puppets are different — built from 10 to 12 layers of papier-mâché (often made from newspapers or pages of Soviet books) and representing at least 120 types of characters.

Visitors to the museum can explore not only the origins and history of Uzbek puppetry, but also the main characters featured in performances. Live demonstrations offer a chance to see the puppets in action — and even to try maneuvering one yourself!

On display, you’ll find a fascinating array of puppets from all walks of life, each imbued with its own personality and expression. I couldn’t help but compare it to the hand puppetry traditions I’ve encountered in Taiwan, Japan, and Sicily. Look closely, and you may discover a puppet whose face mirrors your own, one you’ll want to bring home.

Wanderer’s tips — If you’re lucky, you’ll be invited upstairs to the workshop to witness puppet-making in progress and to explore additional puppets from other parts of the world.

Ohel Itzhak Synagogue

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

A peek into the Ohel Itzhak Synagogue in Bukhara.

Wander further down the same lane that houses the Puppet Museum, and you’ll find traces of Bukhara’s long-standing Jewish community.

Central Asia has been home to Jews for centuries, though the details of their arrival remain debated: some say they arrived via Silk Road trade routes, while others suggest they were relocated to Bukhara during Timur’s reign (1370–1405).

Kuhma Mahalla, Bukhara’s oldest Jewish quarter, is a labyrinth of winding streets and traditional homes. At its heart lies the Ohel Itzhak Synagogue, established in 1800 by Rabbi Yosef Maman and Itzhak Zanbur. Its large prayer hall served as a sacred space for worship until 1938, when Soviet authorities closed it and converted it into a textile factory; from 1952, it served as a dwelling. The building was finally returned to the Jewish community in 1992 and has since been carefully restored.

Today, the synagogue still safeguards a Torah over 500 years old — a witness to the faith and resilience of Bukhara’s Jewish community.

Wanderer’s tips — Just opposite the synagogue, you’ll find a discreet entrance that leads to a Jewish school.

Bukhara Artisan Development Centre

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

Stepping into the Bukhara Artisan Development Centre feels like entering a hidden treasure trove.

When I first read about the Bukhara Artisan Development Centre, I struggled to find its location — it isn’t even listed on Google Maps. I asked my guide, and even he had never heard of it. But perhaps one always finds what one seeks: I was fortunate to stumble upon it by chance.

Established in 1996, the centre — housed in Saiduddin Caravanserai — aims to revive lost crafts and support local artisans. Here, a handful of artisans continue practices passed down through generations, including ikat weaving, traditional suzani embroidery, metalwork, jewellery, miniature painting, and calligraphy.

Last year, I bought an ikat scarf from an old master at a workshop now called Silk & Heritage. On this return visit, I learned the master had returned to his home in Andijan, and the workshop is now run by weaver Nasullobek Rajabox, supported by Daminjon Axunov, a dedicated master weaver who is almost always present whenever I visit.

One of my favourite embroidery shops in Uzbekistan is tucked inside the centre. While suzani products are common throughout Bukhara and other cities, I’m drawn to the rustic, simple designs crafted by Bashkir, the old lady who runs the shop. Pomegranates in various hues bloom among flowers and leaves on cotton tote bags, towels, jackets, and table runners. I didn’t buy anything on my first visit (a decision I regretted), so this time I couldn’t resist an embroidered jacket adorned with this beautiful symbol of abundance and prosperity.

Wanderer’s tips — In the evenings, the courtyard transforms into a lively performance space, where you can enjoy music alongside tea or food served by Aladdin's Lamp.

Magoki Attori Mosque

Sense of Wander: ★★★☆☆

The Magoki Attori Mosque in Bukhara is now home to the Carpet Museum.

Magoki Attori is the oldest mosque in Bukhara, bearing witness to the city’s rich history: its 12th-century structure rises atop a former Zoroastrian temple that dates even further back in time.

While the oldest part of the mosque dates to the 12th century, the upper section was rebuilt in the 16th century. Inside, remnants of furnaces used for fire worship can still be found in a corner, pointing to its original function as a Zoroastrian temple.

The building has two entrances: on the south-west side, the original doorway features terracotta calligraphy and geometric designs, with traces of turquoise-glazed ceramics along the pointed arch — this marks the mosque’s primary foundations. To the east is today’s main entrance, now adorned with newer mosaic decorations.

You might wonder why the mosque sits sunken below the surrounding streets. Over centuries, thick layers of cultural deposits buried it, with the façade only fully excavated in the 1930s.

Today, Magoki Attori now houses the Carpet Museum, displaying exquisite 19th- and 20th-century carpets crafted by masters from Fergana, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, and Iran. During the Bukhara Biennale, the mosque also hosts The Bukhara Archive, curated by the Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF), where visitors can hear stories and reflections on the city’s heritage and time-honoured traditions.

Wanderer’s tips — From here, wander towards Toqi Sarrafon, where a vendor sells shoulder bags and wall hangings made from vintage carpets he has redesigned himself — one of my favourite spots in Bukhara.

Ulugbeg Madrasa

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

The Ulughbeg Madrasa in Bukhara is the first madrasa commissioned by Ulugh Beg.

Ulugh Beg (1394–1449) was the grandson of the great conqueror Timur whose empire once stretched across modern-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, the South Caucasus, and much of Central Asia.

A scholar as much as a ruler, Ulugh Beg distinguished himself in astronomy and mathematics. He built one of the finest observatories in the 15th century, traces of which can still be seen today at the Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand. He also left his mark on education, founding madrasas in both Samarkand and Bukhara.

In 1417, he commissioned his first madrasa in Bukhara, now known as the Ulugbeg Madrasa. Its two-storey courtyard, lined with modest hujra, contrasts with the more elaborate tiled portals and gilded muqarnas of the Abdulaziz Khan Madrasa opposite. Together, the two are traditionally called kosh, or “twin” madrasas.

A detail not to be missed is the inscription carved near the top of the entrance’s wooden door: “Aspiration for knowledge is the sacred duty of every Muslim, men and women.” This simple exhortation taken from the Hadith reflects both the centrality of learning and the inclusion of women in the pursuit of knowledge. Today, the madrasa hosts a modest History Museum of Bukhara Calligraphy Art, alongside a few vendors offering local arts and crafts.

Wanderer’s tips — Look closely at the door, where the master craftsman’s name, “Ismail ibn Takhir,” is carved. He was the son of Mahmud, a master from Isfahan, hinting at the rich lineage of artisans who shaped Bukhara’s architectural heritage.

Poi Kalyan Mosque & Minaret

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

In the early morning, the Kalyan Mosque and Minaret stand free of visitors, radiating a serene atmosphere.

The Poi-Kalyan complex encompasses the Mir-i-Arab Madrasa, the Kalyan Mosque, and the towering Kalyan Minaret, with structures spanning from the 12th to the 16th centuries. Its name — “At the foot of the great one” — pays homage to the imposing minaret, which remarkably withstood the Mongol invasion that swept through Bukhara.

The Kalyan Minaret, a symbol of the city, was built in 1126 by order of Arslankhan, governor of the Karakhanid dynasty (840-1212). Rising nearly 46 metres, with a diameter tapering from 9 metres at the base to 6 metres at the top, its 10-metre-deep foundation ensures stability even in seismic tremors. Beyond calling the faithful to prayer, the minaret also guided caravans arriving in Bukhara, standing as a beacon of orientation in the desert.

Legend holds that when Genghis Khan surveyed the city, his hat fell off as he looked up at the minaret, compelling him to bow. Interpreted as a gesture of respect, the conqueror spared the minaret from destruction, while the original mosque fell to ruin.

The Kalyan Mosque, once the second-largest mosque in historic Uzbekistan, was rebuilt in the 16th century.

Wanderer’s tips — Entrance ticket to the Kalyan Mosque is valid for the entire day. Return at maghrib to witness the prayers, and see the mosque bathed in the light of setting sun.

Ark of Bukhara

Sense of Wander: ★★★★★

Entrance to the Ark, former residence of the Emir of Bukhara.

Like fortresses across the world, the Ark of Bukhara stands as a timeless symbol of power. Once the administrative heart and residence of the Emir of Bukhara, the Ark — meaning “citadel” — also welcomed great scholars and poets, including Rudaki (circa 858–940), Ibn Sina (circa 980–1037), Ferdowsi (940–1020), and Omar Khayyam (1048–1131).

Its origins stretch back at least fifteen centuries, though the details are wrapped in legend. One story tells of Siyavush, who fled his stepmother and arrived at a desert oasis. There he fell in love with the local king’s daughter, who would be his only if he could build a palace within a space defined by a bull’s hide. Cleverly, Siyavush sliced the hide into thin strips, joined them into a circle, and constructed a palace within — giving birth, in legend, to the Ark.

Most of the structure visible today dates from the 16th century under the Shaybanid dynasty (1428-1599). The main gate is flanked by two cylindrical towers, joined by a gallery called Nogora Khona, or “House of Drums,” where musicians would play for the Emir.

The Ark suffered severe damage during the Red Army’s 1920 operation in Bukhara, leaving much in ruins. Today, the eastern half serves as an archaeological site, while the fortress itself still houses the Jami Palace Mosque, a mint, a treasury, a bathhouse, the throne room, and courtyards. Some spaces have been transformed into museums, including the Museum of Calligraphy and the Museum of Decorative and Applied Arts.

Wanderer’s tips — Entrance to the Ark is valid all day. Return at sunset to the archaeological site’s panorama deck and watch the Poi-Kalyan complex glow like a beacon in the evening light.

Bolo-Hauz Mosque

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

Beautiful calligraphy and geometric designs grace the prayer hall of the Bolo-Hauz Mosque.

Across from the Ark of Bukhara stands the Bolo-Hauz Mosque, built in 1712. Legend has it that Emir Shakhmurad (1785–1800) commissioned it for public prayers, drawn by a desire to be among his people, though others suggest it was the wish of the Emir’s wife. Its proximity to the Ark meant that the Emir would occasionally visit, and red carpets were said to mark his path.

A tranquil pond, or hauz, lies in front of the mosque, giving the mosque its name — Bolo-Hauz, “near the pool.”

In the early 20th century, a verandah, or ayvan, was added, supported by twenty elm columns soaring over twelve metres high. The ceiling above is adorned with muqarnas-inspired patterns and multi-pointed stars, painted in the unique hues of Central Asian tradition. From that time, locals affectionately call it Chilstun, or “Forty Columns,” a reflection mirrored in the pond below.

Its minaret was built in the early 20th century by Shirin Muradov (1879–1957), a master artisan of Bukhara, whose hands gave birth to a structure that bears witness to the city’s craft traditions.

Wanderer’s tips — Visit the mosque outside prayer hours. Remove your shoes, step inside, and take a moment to immerse yourself in the serene beauty of its calligraphy and interior designs.

Mausoleum of Ismail Samani

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

A 9th-century gem, Mausoleum of Ismail Samani stands as one of Central Asia’s finest examples of early Islamic architecture.

The Mausoleum of Ismail Samani, often called the Samanid Mausoleum, may be modest in scale, but its presence is no less significant than the nearby Ark of Bukhara.

Just outside the historic centre, this monument dates to the late 9th century and serves as the resting place of Ismail Samani (reigned 892–907), ruler of the Samanid Empire (819–999), which at its height spanned northeastern Iran and much of Central Asia. Under the Samanids, Bukhara blossomed as a centre of arts and sciences, rivaling even Baghdad, the Abbasid capital that thrived as the centre of the Islamic Golden Age.

The mausoleum is a family crypt, holding Ismail himself, his father Ahmad, and his grandson Nasr — a rare exception to Islamic law, which traditionally forbade posthumous monuments.

Its design is elegantly simple: a cube reminiscent of the the Kaaba in Mecca, crowned by a dome that represents the universe. But within this simplicity lies profound complexity. The bricks are arranged in horizontal, vertical, and diagonal patterns that create a mesmerising geometric tapestry across both interior and exterior walls. When sunlight hits the façade, the interplay of light and shadow seems to animate the structure, creating new textures with each passing hour.

Seeing the mausoleum in person is quite a moving experience — a monument I had only known through photographs in Islamic art history class comes alive before my eyes.

Wanderer’s tips — Just outside the mausoleum, you might meet Saidov Sohib, a photographer whose work is featured in Architectural Monuments of Uzbekistan. Across the street, the Talipach Gate, a fragment of the ancient 12-kilometre city wall, is only a five-minute walk away.

Memorial Complex of Naqshbandi

Sense of Wander: ★★★☆☆

Pilgrims and devotees offer prayers within the grounds of the Memorial Complex of Khoja Bakhouddin Naqshbandi.

To the northeast, just outside Bukhara’s city centre, lies the Memorial Complex of Khoja Bakhouddin Naqshbandi. Established in the 16th century to honour the revered Sufi master (1318–1389), the complex has grown over centuries into a place where spiritual devotion and architectural artistry meet.

At its heart rests the tomb of Naqshbandi, founder of the Naqshbandia Sufi Order and spiritual teacher to Timur. His teachings shaped the course of Sufism across Central Asia. A principle of his philosophy — Dil ba joru, dast ba kor (“The heart with God, the hands at work”) — can be found inscribed within the complex.

The mausoleum’s façade, adorned with delicately patterned brickwork and lapis-lazuli and turquoise-hued tiles, draws the eye with understated elegance, while its inner courtyards invites reflection and contemplation among pilgrims and visitors alike.

The complex is huge, encompassing a khanqah, mosques, a minaret, a small madrasa, and a large necropolis where Naqshbandi is buried. Considered the “Central Asian Mecca,” believers from across the regions come here to seek blessings, healing, and the fulfillment of wishes.

Wanderer’s tips — Arrive in the early morning to experience the mausoleum in peace, before the pilgrims begin to flock in.