Mamluks: Legacy of an Empire

A landmark exhibition on Islamic art, Mamluks: Legacy of an Empire shows how a sultanate turned authority into artistry: the precision of metalwork, the confidence of calligraphy, and a design language of its own.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

Inside Mamluks: Legacy of an Empire exhibition at Louvre Abu Dhabi.

ABU DHABI, UAE — I walk into Mamluks: Legacy of an Empire expecting history. Instead, I find myself wandering through power and art.

The Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517) is known for its military power, and the exhibition makes that point immediately. The first object is a Mamluk caparison, said to have been retrieved from the battlefield near the Pyramids. Velvet and silk, gold and silver, lapis lazuli and coral are materials that speak the language of luxury. Looking at it, it’s hard not to imagine how such splendour fed Europe’s long fascination with the East.

For many Europeans, the Mamluks are remembered through one scene: the Battle of the Pyramids on the Giza plateau on 21 July 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte’s forces met Mamluk horsemen. This encounter lives on in paintings — François-André Vincent was among those who helped immortalise the Mamluks in European imagination.

I linger in front of Vincent’s canvas, and right before it another voice takes over: a 19th-century copy of The Romance of Baybars (Sirat al-Malik al-Zahir Baybars), the popular epic of Sultan Baybars (reigned 1260–1277), celebrated as the champion who fought the Mongols and the Crusaders.

It isn’t “history” in the strict sense; it’s history as people carry it. For centuries, Baybars’ story travels through shadow theatre and cafe storytellers in Cairo, Damascus, and Aleppo. In the same gallery, a video installation of shadow play reduces a Mamluk fleet to moving silhouettes — legacy passed on through popular art, through voices, and flickering light.

A sumptuous caparison — horse trappings fit for a Mamluk rider — said to have been taken during the Battle of the Pyramids (1798).

Who were the Mamluks?

Centred in Cairo, the Mamluk Sultanate stretches far — from Egypt across the Hijaz and into Bilād al-Shām, the region we now call Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan. Even the map reminds you this isn’t just a regional story; it’s a whole world.

“Mamluk” means “owned one” in Arabic, a word used for slave-soldiers. Boys — often of Turkic origin at first, and later Circassian — were purchased young and brought into a system that trained them in war and religion. Once freed, they didn’t return to ordinary life; they entered the military hierarchy, rising by skill and loyalty, some all the way to the throne. The key to the Mamluk system is that power rarely passes to sons. It’s a kind of meritocracy — power is earned and constantly renewed through new recruits.

The Mamluks didn’t invent this structure from nothing. Earlier dynasties already relied on imported troops and military slaves to secure rule. But in 1250, the Mamluks stepped out of dependence and into sovereignty.

They assassinated Turan Shah, the heir of Sultan al-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub (reigned 1240–1249), and in the turbulence that followed, Shajar al-Durr (circa 1220–1257) briefly ruled as sultana. Her reign lasted only three months, yet her story continued to inspire later generations — a reminder that the Mamluk world won’t sit neatly within the boundaries we expect.

This early 14th-century beaker hints at a Mamluk privilege: only those of Mamluk identity were entitled to ride horses.

The names that follow are the ones history keeps repeating. Baybars (reigned 1260-1277), the hero of the popular epic, defeated the Mongols at ‘Ayn Jalut in 1260 and revived an Abbasid caliphate in Cairo, a move that turned legitimacy into something you could stage.

Under al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun (reigned 1293–1341, with interruptions), the sultanate entered a golden age. Cairo grew more confident: canals and aqueducts multiplied, bridges went up, and the Citadel was enlarged and reshaped on a grand scale.

Wandering in the exhibition, you would begin to sense that Mamluk power didn’t only announce itself in battle, but in the ability to remake a city.

An copper-alloy incense burner inlaid with gold and silver, bearing the name of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun.

The Mamluks’ control over Mecca and Medina was another pillar of authority. On display is a key to the Kaaba, its surface inlaid with the name of Sultan Faraj (reigned 1399-1412) in gold thread. Nearby, a marble plaque commemorates repairs to the Holy Shrine of Mecca after a devastating fire in 1402. These aren’t just objects, but claims that say: we hold the roads, we protect the pilgrimage, we have a hand on the threshold of the divine.

Later rulers appear like turning points. Barquq (reigned 1382-1399), the first Burji (Circassian) sultan, marked a shift in the dynasty’s composition. Qaytbay (reigned 1468-1496), more celebrated, is remembered for keeping the sultanate prosperous while facing Ottoman pressure. Barsbay (reigned 1422-1438), meanwhile, monopolised the spice trade and turned maritime commerce into state revenue. Around these names, the exhibition keeps returning to the same idea: the Mamluks didn’t simply rule — they managed and built systems that hold.

Key to th Kaaba inscribed with the name of Sultan Faraj.

A Sultanate of Many Faiths

The Mamluks were powerful, but they were also distinct. Language, origin, legal status — even appearance — set them apart from the broader society they governed. Privilege was written into daily life: only men of Mamluk identity were entitled to ride horses.

Turkish was the court’s lingua franca, yet Islam remained the bond tying rulers to their subjects. Within that framework, the sultanate held a layered religious landscape. Muslim, Christian, and Jewish centres existed within the same world, drawing pilgrims and visitors from far beyond Egypt.

Jewish and Christian communities — referred to as ahl al-kitab, or “People of the Book” — were allowed to practice their faith under Islamic law, protected and constrained at once.

A ceramic fragment depicting the “Descent from the Cross” is small, almost easy to miss, yet it showcases how Christian iconography was rendered through Islamic ceramic traditions.

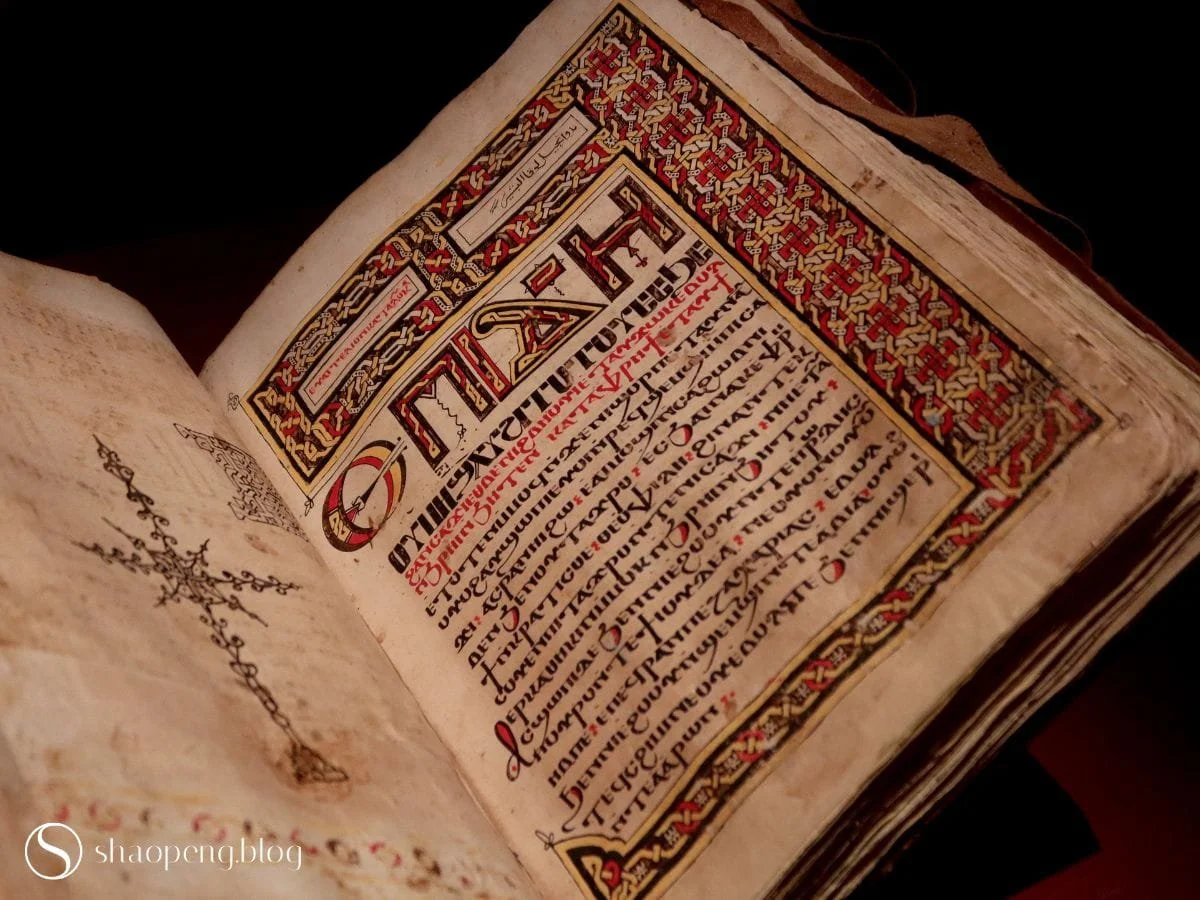

Nearby, a copy of the Four Gospels in Coptic is attributed to Wadi el-Natrun — one of Egypt’s great monastic centres. Produced in the 13th century, the manuscript reminds you that Christian communities continued to copy and preserve books under Mamluk rule. Tolerance here wasn’t a slogan; it’s visible in what survives.

A ceramic fragment depicting the Christian scene of the “Descent from the Cross.”

The Four Gospels in Coptic is a witness to how Christian scripture was still copied and safeguarded under the Islamic-ruled Mamluk Sultanate.

A Multicultural Sultanate

The Mamluk world was connected because geography made it so. The sultanate sat at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, threaded by Silk Road routes, Indian Ocean spice currents, and the pilgrim road to Mecca.

In one corner of the exhibition, a Mamluk bowl is beatifully inlaid with phoenixes — an Ilkhanid motif that made its way into Mamluk visual culture, alongside dragons, cloud bands, and lotus flowers. A peace treaty signed in 1323 with the Mongols helps explain how artistic influences travelled across borders.

Across the Red Sea, Egypt’s ports competed with Aden under the Rasulids of Yemen. The relationship between Cairo and Yemen shifted constantly — cooperative at times, hostile at others — yet patronage continued to travel. A Mamluk glass bottle made for a Rasulid sultan, marked with a rosette emblem, is one of those objects that leaves you thinking: rivalry and admiration could coexist.

Further east, connections with the sultanates of Delhi, the Deccan, and Sri Lanka helped facilitate imports, especially Chinese ceramics. A display case shows exchange in both directions: a Chinese tray stand echoed the shape of Mamluk inlaid metalwork, while a 15th-century Syrian bottle and bowl features Chinese-inspired designs.

A blown-glass vessel inscribed with the name of ʿUmar II, sultan of Yemen.

Inlaid with phoenix imagery, this bowl shows how Ilkhanid motifs travelled into the Mamluk world.

A Chinese tray stand (left), shown alongside a Syrian bottle and bowl, reflects artistic exchange in the 15th century.

The Mediterranean route brought other encounters. Diplomatic relations with the Nasrids of al-Andalus, commercial ties with Italian maritime powers, and the eventual end of papal embargoes opened space for shared taste.

A Venetian-school painting places Mamluk and Venetian figures within the same frame: the governor seated high, surrounded by emirs, as diplomacy turned into theatre.

Over time, Europe developed an appetite for Mamluk art so intense that some objects slipped into Christian ritual life. A 14th-century Mamluk glass beaker, later found as a reliquary in Umbria, was one of those travellers. It depicts a horseman — an image tied to Mamluk identity and privilege. I first saw it during my visit to the Louvre in Paris more than a decade ago; seeing it again now in Abu Dhabi feels like running into a familiar face in a new city.

Textiles made the journey too. Mamluk silks favoured a disciplined layout: ornament arranged in medallions or in parallel bands that feels almost architectural. You’d be intrigued to see a Christian chasuble repurposed with cloth inscribed with the word “sultan” in Arabic, alongside florals and beasts. It’s a reminder that admiration often leads to reuse — the kind that walks the line of cultural appropriation.

Italian workshops learned to copy Mamluk silks, enamelled glass, and copper-alloy wares so well that it eventually put pressure on Mamluk workshops, contributing to a decline in production.

A Venetian Diplomatic Mission Received by the Governor of Damascus (1511)

Patrons of Art

If the Mamluks ruled with the sword, the exhibition insists their legacy was also built through patronage. Sultans, emirs, and wealthy elites commissioned architecture and objects with a seriousness that feels almost political in itself — art as a language of authority.

A section dedicated to the Qalawun complex in Cairo — hospital, madrasa, mausoleum — brings that to life. Commissioned by Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun, it became a masterpiece of Mamluk architecture, known for an ornate design that reshaped the possibilities of funerary space.

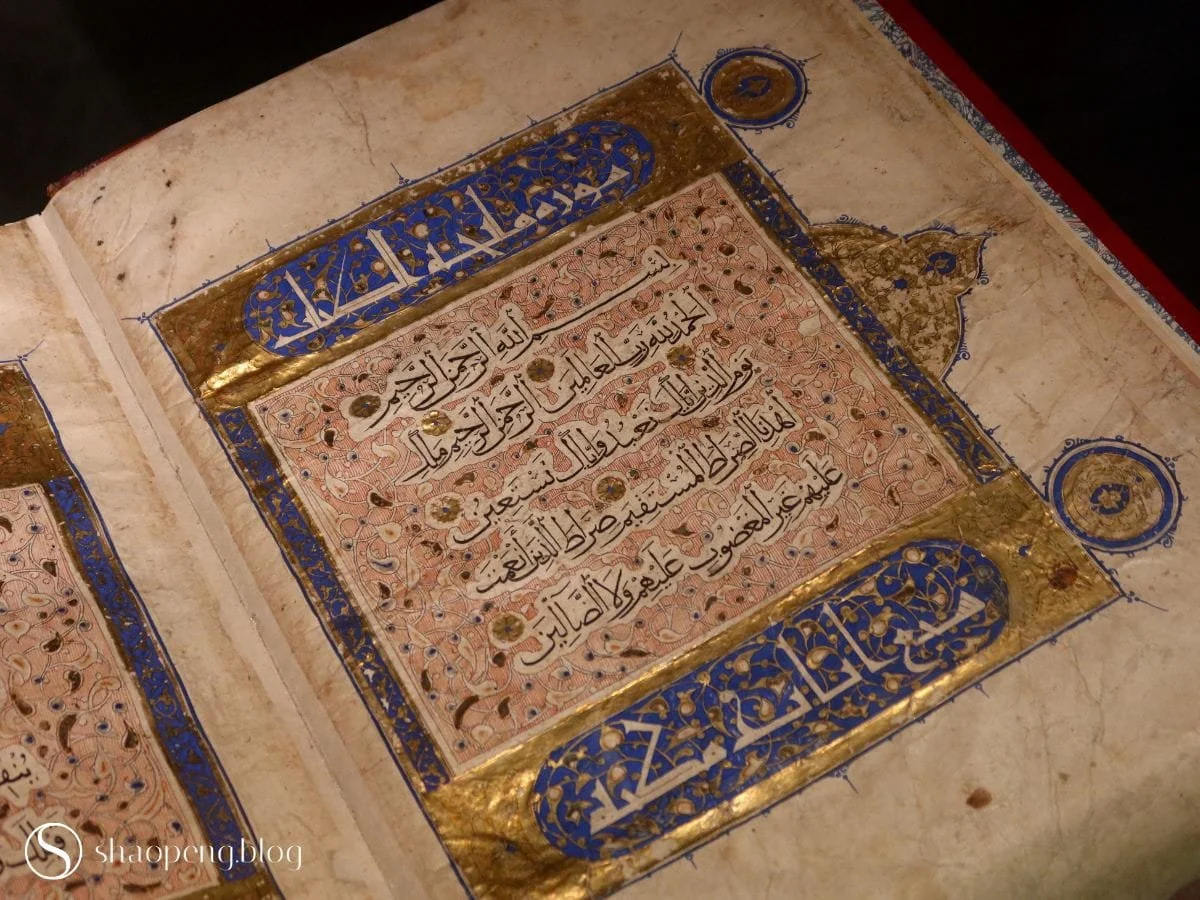

Men weren’t the only patrons. In Cairo, many religious buildings were linked to female patrons, and Sitt Hadaq — also known as Miska — stood out. Once a nurse to al-Nasur Muhammad ibn Qalawun, she amassed wealth through business and later founded a mosque in Cairo in 1340. An illuminated Quran endowed to her mosque is on display, letting her name survive in ink and gold.

Inscriptions on objects commissioned by women were often anonymous or coded, as if visibility itself had limits.

This illuminated Quran was endowed to the mosque founded by Sitt Hadaq in Cairo in 1340.

My favourite part of the exhibition is the section titled “A Mamluk Art,” where the sultanate’s visual world unfolds through calligraphy, wood, metalwork, glass, and textiles. Wandering across the different media, it isn’t difficult to spot a shared design language: bold inscription bands, compartmentalised layouts, disciplined geometry, and vegetal ornament.

Mamluk calligraphy inherited from earlier Iraqi traditions, yet developed its own weight. Thuluth script appears in broader, more assured strokes, often used on monuments and object. Muhaqqaq — a script reserved mainly for Qurans — appears on a double closing page from a monumental manuscript dated to the 14th century. From a distance, it reads as pure confidence. Up close, the letters are seen outlined in gold, and the richly coloured ornamentation hints at royal patronage.

Double closing page from a monumental Quran, dated to around 1360–1380.

An ivory plaque carved with an inscription in thuluth script, framed in wood-and-ivory marquetry.

Mosque lamp inscribed with the name of Emir Qawsun and his blazon — a cup marking his role as cup-bearer.

Cylindrical ivory box with intricate openwork, inscribed with the name of Sultan al-Salih (reigned 1351–1354).

This “Castellani Carpet,” made in 15th-century Cairo, survives in remarkably good condition.

Gold bangle inscribed with the word “prosperity,” dated to the 13th–14th century.

Metalwork, in particular, reached a zenith in the Mamluk period. Inlaid copper-alloy objects — candlesticks, basins, ewers, bowls, penboxes — turned utility into splendour. Surfaces filled with calligraphic inscriptions, figures, heraldic blazons, and scenes of courtly life.

And then there’s the most lavish — and most mysterious — of them all: the Baptistère de Saint-Louis. It later served as a baptismal font for French royal infants, including Louis XIII (1601-1643), but its original patron remained unknown. Instead, it was the maker who insisted on being remembered: Muhammad ibn al-Zayn signed his name in six places.

The final gallery is dedicated to this basin, enlarging its details so the eye could linger on what the mind usually rushed past: the gold and silver inlay, the fine engraving, the niello accents, the miniature drama of figures rendered with astonishing precision. Power is everywhere in this exhibition — but here, it feels almost secondary to the skill that gave it form.

Mamluks: A Legacy Within Reach

An exhibition like this could make you think you are walking through a sealed chapter — from 1250 to 1517, rise and fall, end of story. But the longer I stay, the more I feel the Mamluks refusing neat closure.

Their rule did end in 1517 with the Ottoman conquest, but the Mamluks didn’t vanish overnight. Many joined the Ottoman military and, throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, reasserted influence in Egypt. Ali Bey al-Kabir, for instance, pushed autonomy so far that he even minted coins in his own name.

By the time Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, Mamluk beys still dominated the country in practice. Even after the French withdrawal, Mamluks remained central to Egypt’s power struggles, competing with Ottoman forces and each other. The decisive break came in 1811, when Muhammad Ali Pasha orchestrated the Citadel massacre in Cairo on 1 March, giving the final blow to the Mamluk elite.

The Mamluks may have disappeared as a political force, but Cairo has kept their silhouette. Today, the city’s skyline still carry their imprint. Wander into Historic Cairo and you could feel it in scale and interruption — minarets cutting into the sky, carved stone slowing your pace, monuments still setting the proportions of the present. Their legacy isn’t only what history remembers, but what the city still refuses to forget.

Inside the exhibition gallery “A Mamluk Art.”

Reference:

Juvin, C. (Ed.). (2025). Mamluks: Legacy of an empire [Exhibition catalogue]. Kaph Books.

Mamluks: Legacy of an Empire is on view at Louvre Abu Dhabi until 25 January 2026.