Spotlight on Jewellery: Bukhara Museum

The Bukhara Museum invites you into a world of traditional jewellery, worn not only to beautify the body but to tell stories of devotion, identity, and artistry.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

Tuf-jamalak, a delicate hair ornament once worn by women in Bukhara

BUKHARA, Uzbekistan — Jewellery in Bukhara traces its roots back into antiquity. One of the earliest archaeological findings comes from the burial of a Sak noblewoman: her gold earrings, set with carnelian bead, were shaped like amphorae, while the centre of her headdress held a gold medallion embossed with the face of a Hellenistic goddess.

This glittering chapter of history, born in antiquity, continued to live on in Bukhara. At Toqi Zargaron, the 16th-century jewellers’ dome, the air once rang with the shaping of metal sheets and the careful weighing of stones. Today, it remains the largest of the three surviving bazaars, though its former splendour has softened, replaced by stalls of spices and souvenirs.

By the 19th century, Bukhara had become one of Central Asia’s great jewellery centres, alongside Khiva, Samarkand, Karshi, and Kokand. The tradition we now recognise as Bukharan jewellery flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries — a time of exquisite craftsmanship and cultural expression. Step into the Bukhara Museum within the Ark and you enter that world: silver gleaming like moonlight on silk, and gemstones whispering stories of identity, devotion, and artistry.

The Bukhara Museum holds a rich collection of women’s jewellery from the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Bukhara Museum houses more than two thousand objects in its decorative and applied arts collection, many of them once belonging to the Emir of Bukhara. Among these are men’s and women’s jewellery from the 19th and 20th centuries, not only from Bukhara, but also from Turkmenistan, the Middle East, and beyond.

As you enter the first gallery, a series of glass cases introduces the jewellery traditions that Bukhara shared with other regions of Uzbekistan.

Bukharan women’s traditional jewellery includes head ornaments such as the tilla-qosh (the bride’s crown), temple pendants like mohi-tillo (or bibishak) and gajak, as well as breast decorations such as zebi-gardon and nozi-gardon. Earrings of various styles, including barg, kundalsoz, and halqa, complete the ensemble.

A bride’s attire was a testament to the rich heritage of jewellery, adorned from head to toe. These pieces were worn over the famed Bukharan gold-embroidered zarchapon and traditional Uzbek mursak dresses, creating a radiant display befitting her most auspicious day.

Tilla-qosh, a forehead ornament, exemplifies the richness of Bukhara’s jewellery tradition.

This noycha-tillo, an adornment worn at the temples, is embellished with coral, turquoise, and carnelian beads.

The tilla-qosh (“gold eyebrows”) was a mark of luxury: a tiara shaped like a unibrow and often set with turquoise. Scholars note that its design may have been inspired by Indian traditions popular among both Uzbek and Tajik women.

The tilla-bargak, in contrast, shows tribal influences. This forehead ornament features tiny pendants that sway gently as the wearer moves, catching the light with each step.

A highlight of the collection is a curious type of temple ornaments known as noycha-tillo. Each piece takes the form of a tube, crafted from thin metal sheets and set with semi-precious stones such as turquoise, coral, and carnelian. Threads of gold pass through the tube, and delicate tassels of coral beads, petal-shaped pendants, and sometimes coins hang from its opening. At the centre rests a sphere representing a pomegranate — a motif beloved by Bukharan jewellers, often rendered in filigree or set with gemstones. Traditionally, married women attached noycha-tillo to their braids or headband, letting it hang elegantly from the temple.

Women in Bukhara also embellished their hair. Artificial braids made of fine threads were plaited into natural hair and decorated with beads, creating a fuller and more ornate look.

These hair ornaments, known as soch-popuk or tuf-jamalak, feature long strands of “hair” fashioned from black cotton threads, silk cords, or wool — its length sometimes reaching as far as the knee. Their ends are decorated with beads, tassels, or tiny pendants in myriad designs. Beyond beauty, these adornments also served to conceal hair or draw attention away from it, in keeping with cultural notions of modesty.

Triangle-shaped amulet crafted with silver coins and coloured gemstones.

One of a pair of bozuband, a type of traditional amulets.

This marjon amulet, dating from the late 19th century, displays the artistry of traditional techniques, such as granulation, filigree, and stamping.

Jewellery in Bukhara, as in many great cultures, did far more than adorn the body; it signified status, wealth, and cultural identity, while also serving a protective purpose.

Amulets held a particularly sacred role. In Bukhara, they were believed to shield their wearer from misfortune. Large jewellery sets worn during weddings, for instance, were thought to ward off evil spirits, while coloured gemstones protected against the evil eye. Some pieces were crafted to guard specific parts of the body: rectangular and triangular pendants safeguarded the chest, while bozband and kultikumar amulets shielded the armpits, an area thought vulnerable to harmful forces.

Even decorative motifs carried meaning. The nozigardon, a type of chest ornament, often features delicate fish-shaped pendants, historically believed to enhance a woman’s fertility. Arabic inscriptions, engraved into gemstones or onto precious metal, also adorn amulets, as if whispering prayers through metal and stone.

Gemstones, too, held protective and healing properties. Pearls were prized for their restorative power; carnelian (khakik) was believed to bring happiness and health; and turquoise (feruza) was valued for uplifting the spirit, improving eyesight, and offering victory in battle. This explains why scabbards for swords and daggers were often inlaid with turquoise.

This nozigardon, a traditional pectoral jewellery, features intricately crafted silver birds and fish.

Traditional Bukhara jewellery, featuring calligraphic inscriptions that trace the pendant’s border and extend across the gemstone’s surface.

You may be surprised to learn that the making of jewellery was considered potent. Since ancient times, Bukhara’s master goldsmiths worked with gold — associated with the sun, strength, and masculine energy — and silver, linked to femininity and the moon. The jeweller, or zargar, held a sacred position: each strike of the hammer and exposure to the “sacred flame” carried ritual significance.

This spiritual dimension, however, began to fade during the Soviet period, when craftsmanship shifted towards form and decoration rather than symbolism and protection.

In Bukhara, earrings were often circular, with three, five, or seven delicate pendants. Some featured a dome-shaped design, reminiscent of the jhumka earrings of Indian tradition.

Local beliefs held that rings and bracelets helped keep the hands clean. Bracelets were traditionally worn in pairs and often adorned with carved patterns (dasptona) or intricate openwork (shabaka).

A pair of dome-shaped silver earrings, featuring intricate granulation work.

One of a pair of silver bangles, with green and blue enamels accentuating the nature-inspired openwork design.

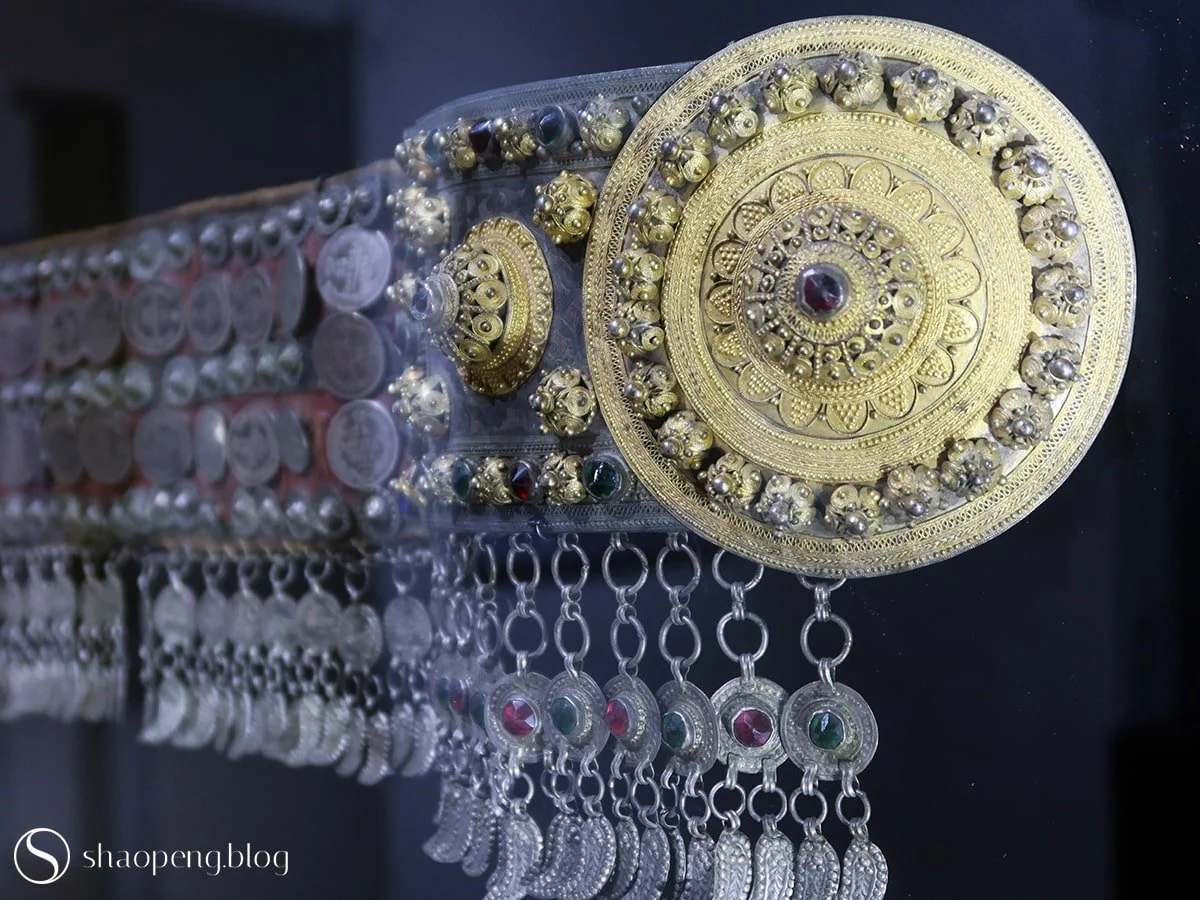

Besides women’s jewellery, the museum also exhibits jewellery for men, particularly the luxurious sashes and belts worn over festive or ceremonial robes. The Emir’s belt, for instance, is crafted from leather or fine brocades and often embellished with silver or gold overlays. Precious stones and gilded silver pendants, believed to hold talismanic properties, further adorn the belt.

For those interested in costumes, a highlight of the collection is the gold-embroidered dress known as peshkurta. Equally intriguing is the paranji in a mesmerising purple hue, its open neckline embroidered with traditional motifs. The paranji, a type of traditional women’s outerwear, consists of a robe and a face covering made of black horsehair called chachvon. It was worn by city women and affluent villagers until the 1930s.

The museum also showcases a few examples of skullcaps (tyubeteika) fashioned from gold threads. While skullcaps are common across Central Asia, those from Bukhara are particularly admired for their exquisite embroidery, forming patterns known as “nightingale’s eye,” “sparrow’s tongue,” and star motifs. These designs not only reflected the wearer’s status but were also believed to offer protection.

A kamaband belt dating from the late 19th to early 20th century.

Robes woven with golden threads are a hallmark of Bukhara’s celebrated embroidery tradition.

Traditional Bukharan jewellery is not a relic of the past; it continues to sparkle in the present. Wander through Toqi Zargaron, and you’ll discover a selection of stalls where handcrafted jewellery inspired by centuries-old traditions.

For a deeper dive, head to the jewellery stall inside the Abdulaziz Khan Madrasa, just opposite the Ulugbeg Madrasa. Here, vintage works sit alongside contemporary interpretations, each crafted by the hands of skilled artisans. The collection features not only Uzbek designs but also creations from neighbouring regions across Central Asia. You’re more than welcome to take home a piece of portable culture that celebrates the artistry and heritage of the region’s jewellery traditions, whose voice is often left unheard in mainstream narratives.

Master jeweller Mirakov at work, captured in a black-and-white photograph at the Bukhara Museum.

Reference:

Abdukhalikov, F. F., Rtveladze, E. V., Ismailova, J. Kh., & Levteeva, L. G. (2021). The collection of the State Museum of the History of Uzbekistan. Part 2: Ethnographic collection (Illustrated vol.). Tashkent: Zamon-Press-Info Publishing House.

Abdukhalikov, F. F., & Rtveladze, E. V. (2022). Traditional Uzbek costumes: The collection of Uzbekistan museums and private collections (Part 1). Tashkent: Zamon-Press-Info Publishing House.

Abdullayev, T., Fakhretdinova, D., & Khakimov, A. (1986). A song in metal: Folk art of Uzbekistan. Gafur Gulyam Art & Literature Publishers.