Wander in Bukhara: Where Calligraphy Lives in the Everyday

Bukhara, a rising destination for calligraphy lovers, is not only home to two museums devoted to the art but also a cradle where its legacy continues to live and breathe.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★★

Surah Al-Fatiha is embroidered in gold and silver threads, forming the shape of Noah’s Ark.

BUKHARA, Uzbekistan — Wandering through the historic heart of Bukhara, one often finds calligraphic inscriptions adorning the facades of mosques and madrasas. Every stroke, every turn of the line, whispers centuries of devotion and artistry.

But how did all begin?

When Islam reached Central Asia in the 8th century, Arabic became the language of scholarship and official record. Writing soon transcended its role as a medium of communication — scribes and calligraphers began to seek beauty in every letter, harmony in every stroke. Over time, calligraphy found new expressions, extending beyond parchment and paper to adorn objects of daily life across the region.

Writing allowed passion and knowledge to travel through space and time. But in Islam, calligraphy is more than an art — it’s the sacred means of transmitting the divine word of the Quran, and thus, regarded as the highest of all artistic forms.

Central Asia has long nurtured the art of calligraphy. From the 14th century onward, five major schools emerged — those of Bukhara, Khorezm, Fergana, Samarkand, and Tashkent.

During the reign of Ubaidullah Khan in the 16th century, Bukhara became a hub of calligraphy. The Khan brought masters such as Mir Ali Heravi (1456-1544) from Herat, a pivotal figure whose teachings shaped the course of calligraphy in the region. Heravi spent sixteen years in Bukhara, where he trained a generation of calligraphers and left behind a lasting influence on the city’s visual culture.

Among those who followed was Mir Ubaid Bukhari (d. 1601), who developed a new style of Naskh script celebrated for its clarity and grace. Generations of calligraphers across Transoxania would later emulate his hand, giving rise to what became known as Naskhi Bukhoriy, or “Naskh of Bukhara.”

The Bukhara school of calligraphy rose to prominence through the works of these masters. The art was admired not only for its script but also for the harmony between text, paper, and miniature. For the finest manuscripts, calligraphers used abribahor paper — a marbled paper prized for its ethereal, cloud-like patterns.

The Djami Mosque, situated within the Ark of Bukhara, now houses an exhibition dedicated to calligraphy.

Inside the Ark of Bukhara, the former royal citadel, stands the Djami Mosque, built during the reign of Emir Subhan Qulikhon (1680–1702). Its wooden ayvan, upheld by towering wooden pillars, invites those drawn to the art of calligraphy to step inside, where an exhibition titled Inscriptions of the 16th to 20th Centuries presents to manuscripts and calligraphy works.

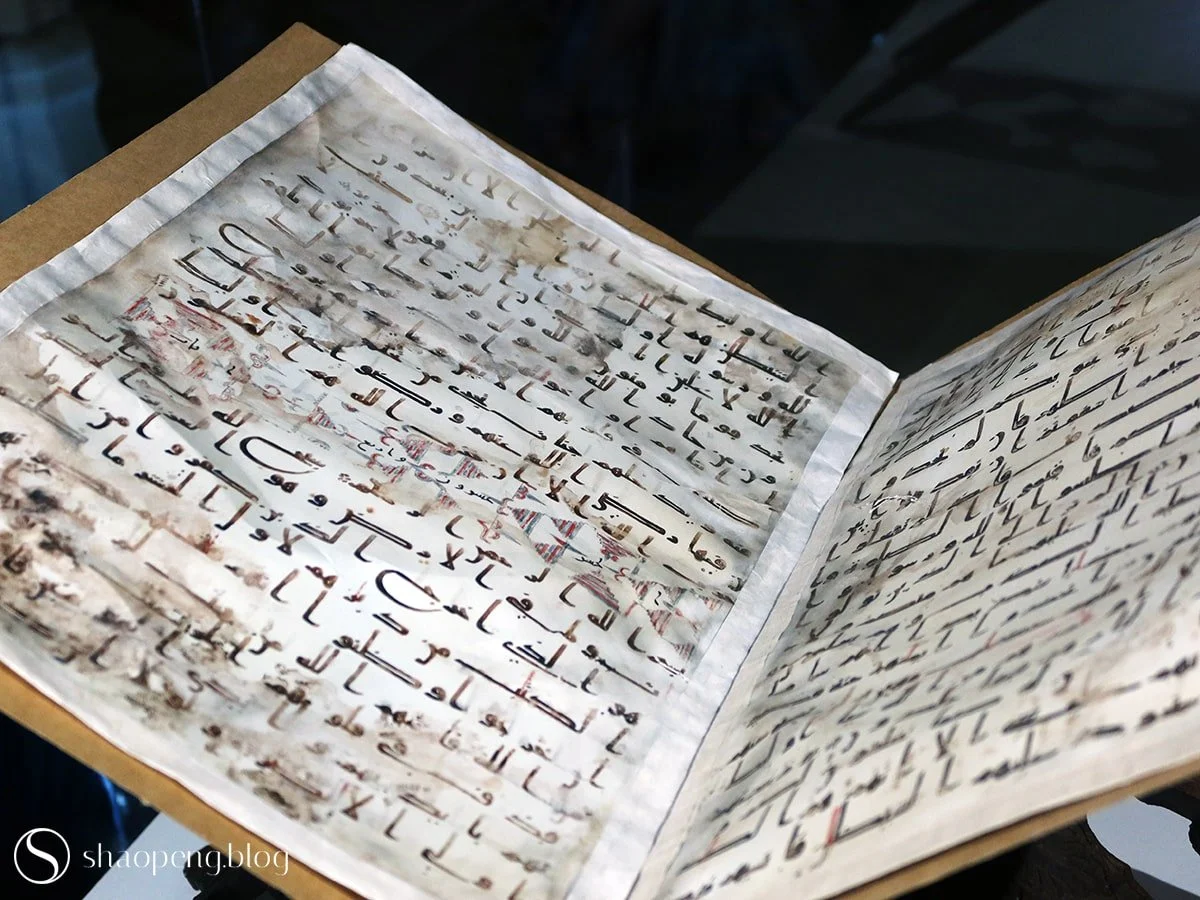

At the heart of the room rests one of its greatest treasures — folios from the Langar Quran, dating to the 8th century. Among the oldest surviving Quranic manuscripts, these pages, inscribed in early Kufic-Hijazi script, were once kept in the Langarota Mosque in Uzbekistan’s Qashqadaryo region.

Calligraphic inscriptions in Thuluth and Kufic adorn the mihrab inside the Djami Mosque.

Folios from the 8th-century Langar Quran feature verses from Surah Al-Mujadilah and Surah Al-Hashr.

A 17th- to 18th-century manuscript in Nastaliq script by the calligrapher Abdurashid.

Throughout the exhibition, the versatility of calligraphy quietly speaks for itself. One remarkable piece, created in 1917 by Mullo Mirzo, blurs the line between script and ornament. By extending and intertwining the strokes of Arabic letters, he created delicate buds and blossoms amid winding vines, all against a soft pink background — transforming sacred calligraphy into a language of everyday beauty.

Nearby, a collection of pocket Qurans is displayed, each enclosed in its own custom-made case. One particularly intriguing example, no larger than the palm of a hand, features a cover set with a brown agate inscribed with intricate calligraphy.

This piece reveals the versatility of calligraphy, where the hand of a skilled calligrapher called Mullo Mirzo dissolves the boundary between word and ornament.

The cover of a pocket Quran case is inscribed with calligraphy in different styles.

Besides writing them, calligraphy was also embroidered. One such work features verses from Surah Al-Fatiha, arranged in a composition that resembles Noah’s Ark. Made in the early 20th century, this gold embroidery is a fine example of Bukhara’s craft.

Within the Djami Mosque itself, calligraphic inscriptions remain visible along the upper walls and around the mihrab, where Kufic and Thuluth scripts come together to convey words of faith.

Before leaving the Ark, visit the Reception and Coronation Courts, the open-air courtyard where coronations were once held. Facing the Emir’s throne, the portal is beautifully ornamented with intricate mosaics bearing Square Kufic, Naskh al-Bukhari, and Nastaliq inscriptions in baked brick and glazed tiles. Their geometric precision evokes a modern, almost digital rhythm — and the Square Kufic, in particular, reminds me of a QR code.

Calligraphic inscriptions in baked brick and glazed tiles adorn the Ark’s Reception and Coronation Courts.

Calligraphy in Bukhara is not confined to parchment and paper; it flows into the objects of everyday life. Many of these works are preserved at the lesser-known History Museum of Bukhara Calligraphy Art, housed within the Ulugbeg Madrasa.

True to its name, the museum invites those who wish to trace the rise of the Bukhara school of calligraphy and its influence across the wider landscape of modern Uzbekistan.

On display is a variety of crafted objects bearing calligraphic inscriptions — from woodcarving and ceramics to metalwork, embroidery, and architectural fragments.

Among these, the Samanid-style plates stand out for their abstract, minimalist beauty, a timeless appeal that resonates even today. Concentric inscriptions are akin to the hands of a clock, gently marking the passage of time. These words are never just decoration but carry wisdom and teachings central to Islam. One reads:

“A thankful eater is comparable to one who fasts patiently.”

The Ulugbeg Madrasa houses a modest museum dedicated to the history and art of calligraphy in Bukhara.

A display of Samanid-style ceramics inside the History Museum of Bukhara Calligraphy Art.

A 19th-century robe embroidered with verses from Surah Al-Fatiha in gold and coloured threads.

While the items on display offer a sense of how calligraphy permeated daily life in Bukhara, most visitors may struggle to connect the objects with the brief explanatory texts. In my view, a deeper, more contextual exploration of Bukhara’s calligraphic tradition — including its influence on other regional schools — would further enrich the visitor experience.

Before exiting the madrasa, look up at the inscription carved on the entrance door:

“Aspiration for knowledge is the sacred duty of every Muslim, men and women.”

This simple Hadith captures the spirit of learning and inclusivity, as well as the enduring role of calligraphy as its messenger.

The entrance door of the Ulugbeg Madrasa is carved with a Hadith that emphasises the importance of education for men and women alike.

Few visitors to Bukhara leave without seeing the Poi-Kalyan Complex, with its towering minaret and the Mir-i-Arab Madrasa, where calligraphy remains part of the school curriculum. Though access to the madrasa is limited, those curious about the art’s living practice can visit Al-Manar, an educational centre just across the plaza.

Even outside class hours, Al-Manar is alive with the presence of calligraphy — dedicated works hung along the gallery walls reminding us that in Bukhara, the art of writing still lives in the everyday.

Opposite the Poi-Kalyan Complex stands an education centre devoted to the teaching of Arabic and calligraphy.

Calligraphy works on the walls of Al-Manar’s classrooms invite students and visitors alike to appreciate the art of writing.

Reference:

Djuraev, K. K. (2021). History of the Bukhara school of calligraphy and its influence on cultural life. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(2), 353–358.