Tracing Her Path: Women Calligraphers in Taiwan and Beyond

Women calligraphers in Taiwan have been walking their own paths. For too long, their presence went unnoticed, until a recent exhibition brings it into view.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★☆

Album cover by Chang Li Der-Her (1893–1972), bearing her studio name “Hostess of Linlang.”

TAOYUAN, Taiwan — In 2024, Taiwanese calligrapher Tong Yang-Tze’s bold, monumental work swept across the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) like a gust of ink-charged wind. Dialogue, the first commissioned piece by a Taiwanese artist in the Met’s history, embodies Tong’s lifelong pursuit: to propel a millennia-old tradition into the pulse of contemporary art. Her strokes — expansive, commanding, unmistakably modern — push Chinese calligraphy into realms it has never dared to go.

“Ask someone to name a Taiwanese woman calligrapher, and Tong Yang-Tze is often the first — and the only — name they can think of,” says curator Lu Hui-Wen, Director of the Graduate Institute of Art History at National Taiwan University. This absence, this blank chapter in the history of calligraphy, forms the heart of Walking Their Own Paths, an exhibition devoted to restoring women calligraphers to the narrative they helped shape.

The exhibition grew out of a 2022 survey of Taiwan’s contemporary women calligraphers commissioned by the Taoyuan Museum of Art. During their research, Lu and her co-researcher Chuang Chien-Hui discovered an astonishing truth: despite Taiwan’s rich calligraphy scene, no systematic study had ever been done on women practitioners. Determined to fill this void, they undertook an ambitious body of research, which eventually took form as this landmark exhibition — the first of its kind in Taiwan.

There is no more fitting venue for this story to be told than the Hengshan Calligraphy Art Centre (HCAC), Taiwan’s first public institution dedicated entirely to the study, preservation, and innovation of calligraphy. Walking Their Own Paths features works spanning nearly a century, and unfolds across paper, mixed media, installation, photography, and video. These Taiwanese artists stand in dialogue not only with each other, but also with women artists from Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, bringing together women’s creative voices from across cultures.

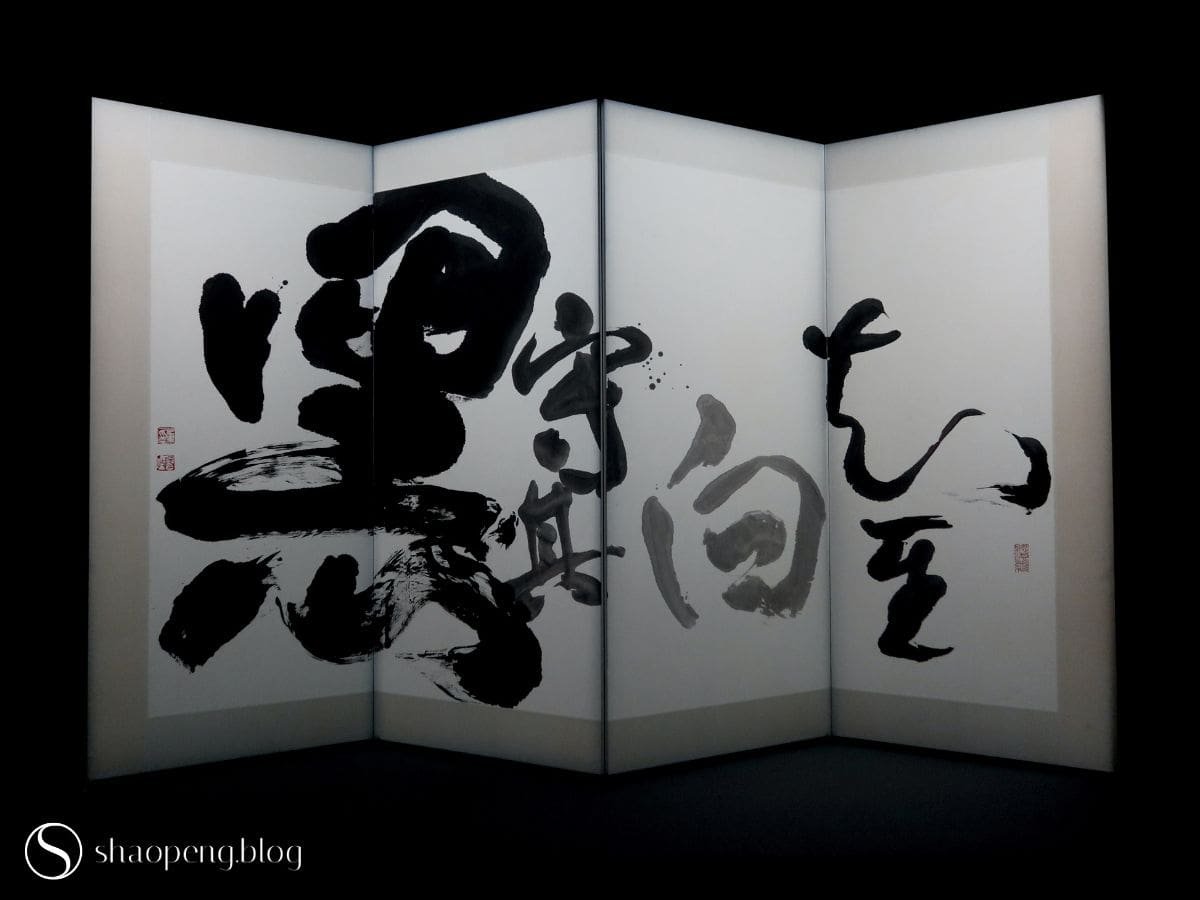

Know It’s White, Keep Silent When It’s Black by Tong Yang-Tze

Few would imagine that women calligraphers were already active in Taiwan as early as the Japanese colonial period (1895–1945). One such presence was Chang Li Der-Her (張李德和) of Chiayi, born into a prominent family in Xiluo. Admired for her versatility in poetry, prose, painting, and calligraphy, Chang became a vital figure in the cultural circle of her time. On view is an album cover bearing her studio name, “Hostess of Linlang,” a title that hints at her artistic philosophy. The album gathers 24 fan paintings and calligraphy pieces by the luminaries who frequented Chang’s salon, testifying to her influence and to the cultural exchange of the era.

After 1949, as the Nationalist government relocated to Taiwan, figures such as Zhang Mojun (張默君) and Tan Shu (譚淑) brought with them the classical traditions of Chinese calligraphy. In the post–martial law era (after 1987), artists like Tong Yang-Tze (董陽孜) and Cheng Fang-Ho (鄭芳和) began to challenge established boundaries with avant-garde experimentation and conceptual boldness.

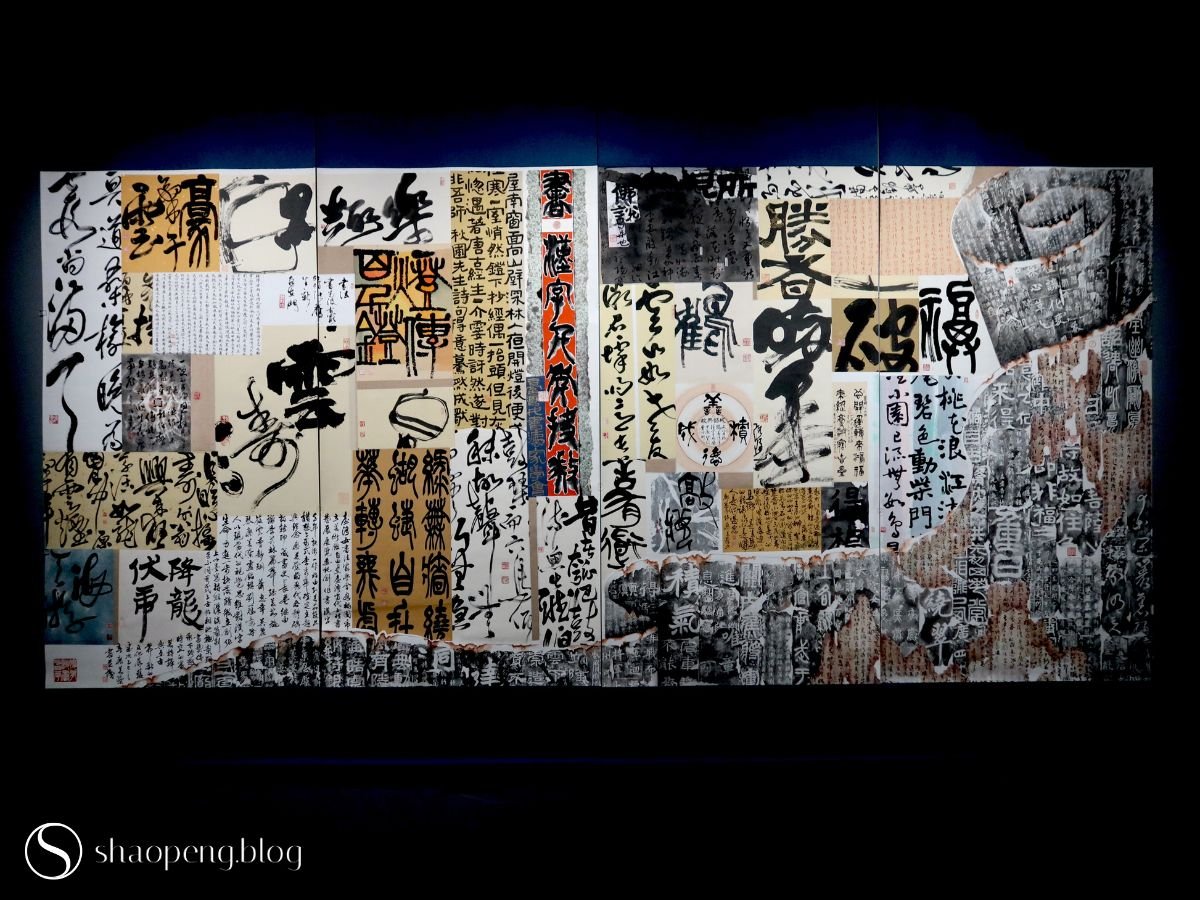

One stunning display is a large collaborative canvas by the Taiwan Women Calligraphers’ Association, featuring works by ten members ranging from their 40s to their 80s. Seal, clerical, standard, running, and cursive scripts coexist on the same surface — not in competition, but expanding the horizon with inclusivity and shared strength.

Calligraphy Writing: The Hidden Depths of Chinese Characters Through Millennia by Taiwan Women Calligraphers’ Association

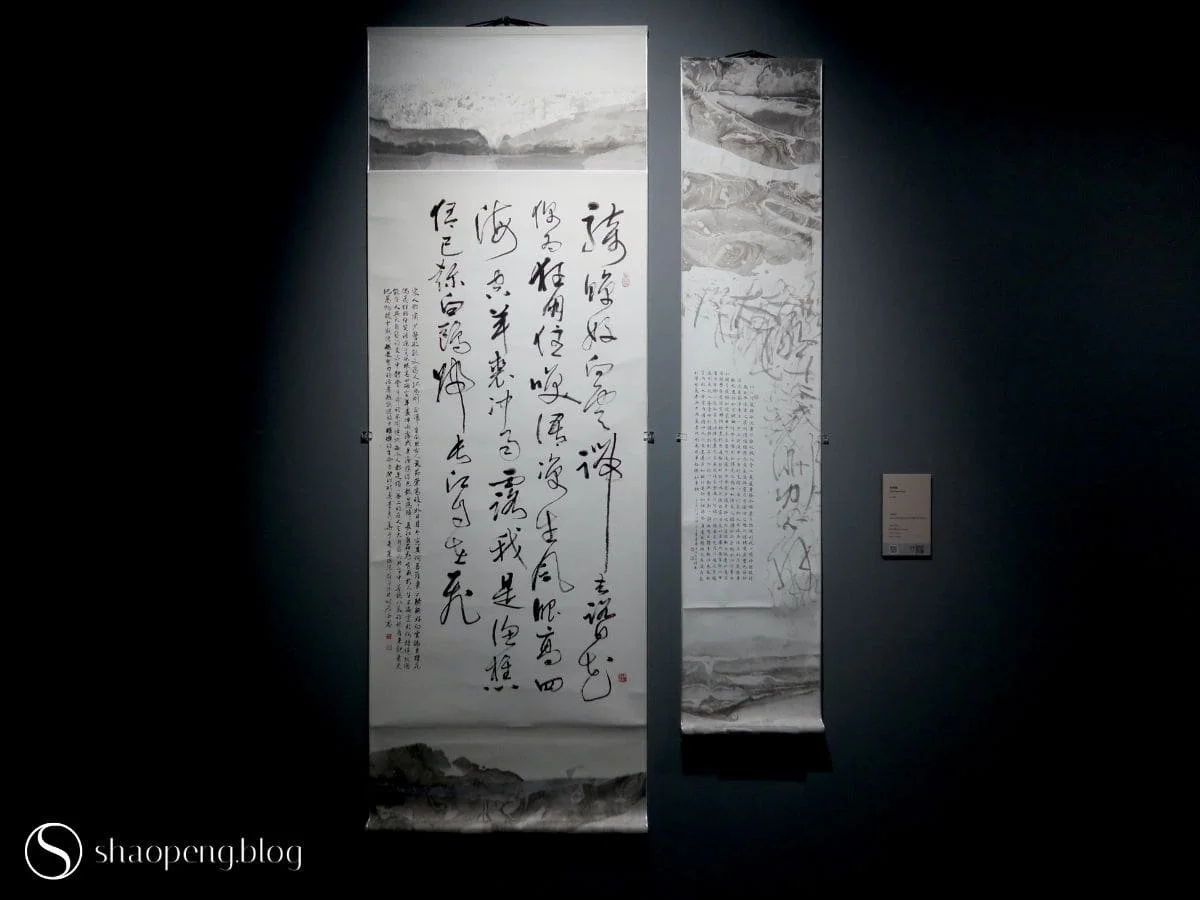

Suite of Flowing Ink and Calligraphy Writing by Lee Shew-Hua

Among the many works on view, I’m particularly drawn to the work by Lee Shew-Hua (李秀華). In Suite of Flowing Ink and Calligraphy Writing, Lee’s proficiency across a wide spectrum of scripts is evident. However, it’s the atmospheric ink washes at the top and bottom of her hanging scrolls that catch me off guard. Soft, cloud-like, and meditative, these misty landscapes bear a resemblance to ebru, the marbled art believed to have originated in Central Asia.

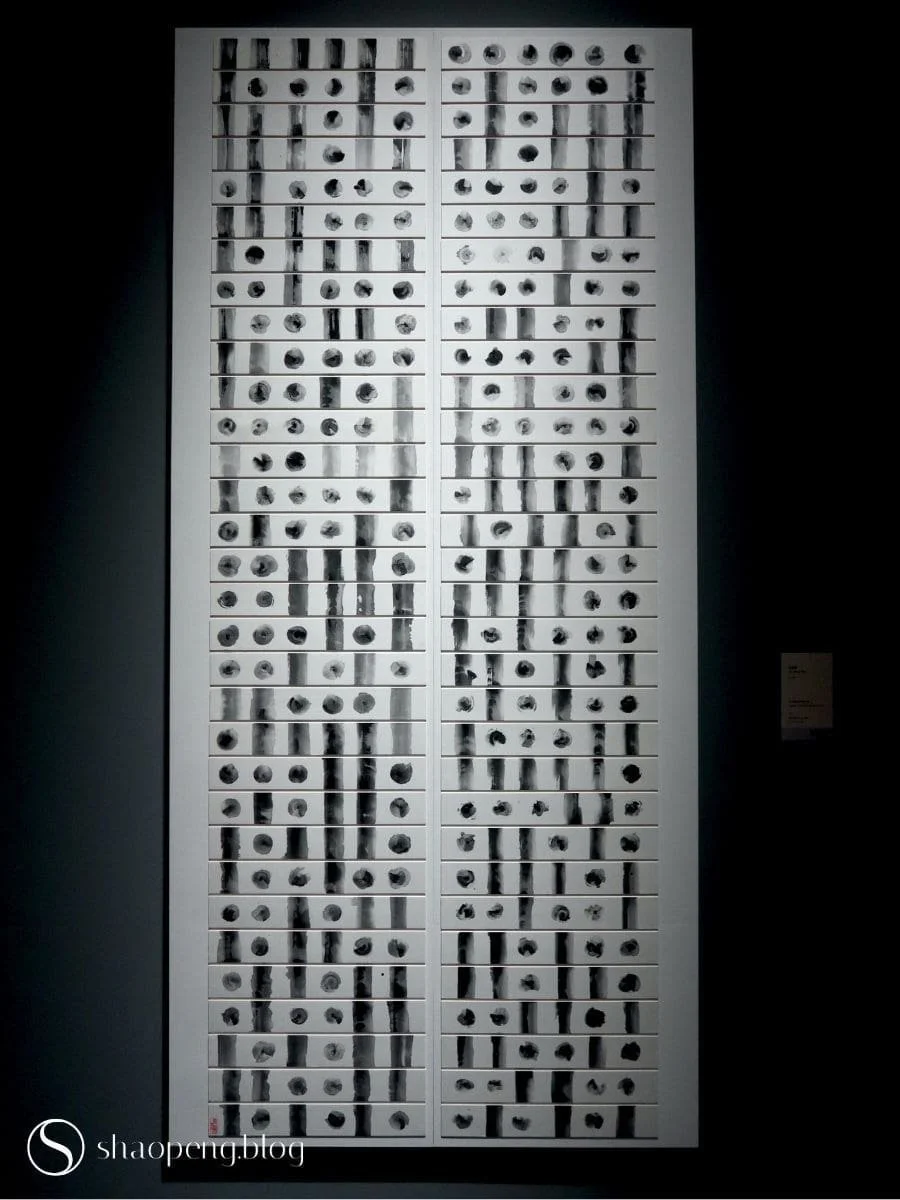

In contrast, Wu Meng-Shan (吳孟珊) transforms calligraphy — a tool for expressing written language — into symbolic imagery. In Leibniz’s Calculating Machine March, she translates the 64 hexagrams of the Book of Changes into sequences of zeros and ones, creating an unexpected philosophical dialogue between East and West. Each digit is rendered with its own energetic brushstroke, and the stroke for “one” in particular evokes bamboo, bringing to mind the shared origins of painting and calligraphy — an idea popularised in ancient China.

Leibniz’s Calculating Machine March series by Wu Meng-Shan

My favourite among the contemporary works is a monumental canvas by Jiang Bo-Xuan (江柏萱), titled 10,000 Ways to Be Free. The artist repeatedly writes the characters ziyou (freedom) in gray ink — sometimes legible, sometimes tilted, stretched, or tangled. The repetitions morph into a visual mantra, embodying a restless, unbound spirit. It’s delightful to see how Jiang’s strokes leap beyond her rigorous academic training — in a culture where methods and principles of calligraphy are highly emphasised — and dance beyond the confines of tradition.

10,000 Ways to be Free by Jiang Bo-Xuan

What makes this exhibition special is the dialogue it creates between Taiwanese artists and their international counterparts.

In The Forest of Wisdoms, Korean artist Kang Misun transcribes a character from the Diamond Sutra on each 10-centimetre square of layered Korean xuan paper dyed in persimmon juice. Each square — humble and earthy in texture and colour — resembles a tree’s growth ring; together, they create a forest that invites contemplation.

The Forest of Wisdom by Kang Misun

Manuscript of Nature V_F.W.X. by Cui Fei

New York–based Chinese artist Cui Fei turns to nature rather than brush to explore the origins of writing. Her Manuscript of Nature series uses vine tendrils, leaves, and thorns to create compositions reminiscent of Chinese calligraphy. Shadows cast by the materials add a sculptural dimension, linking the act of writing back to its ancient root: observing the rhythms of the natural world.

Work by Japanese artist Shinoda Toko (1913–2021), a key figure in postwar dialogue between Eastern and Western abstract art, is on display, showing how her mastery of traditional calligraphy laid the foundation for her avant-garde abstraction, which embodies Japanese aesthetics.

Also from Japan is Kawao Tomoko, whose Hitomoji series captures ephemeral moments by translating the stories of real individuals through a combination of calligraphy and photography. Kawao begins by interviewing the subject, then selects a single-letter kanji inspired by their story, and finally invites the participant to complete the character with their own body. Inside the exhibition, visitors can watch videos in which the interviewees share their life stories, values, and experiences, explaining how the character was chosen.

Through this process, Kawao transforms calligraphy — often a flat, two-dimensional form on paper — into a medium that engages directly with social realities and human experiences. I find the project quite inspiring because it conveys stories of women from around the world: to date, Kawao has created over 30 works across more than 20 countries. Each piece is a living portrait that resonates far more deeply than any magazine cover could, allowing the subject’s voice be heard.

Hitomoji Project - Women by Kawao Tomoko

One of the most thought-provoking moments in the exhibition is my encounter with Peng Wei’s Hi-Ne-Ni Heart Sutra I. The figure’s torso, built from layers of xuan paper — first wrapped around a cast human form and then peeled away like a cicada slipping from its shell — commands attention. Its surface is covered with inscriptions from the Heart Sutra, rendered in varying shades of ink. In Hebrew, “Hi-Ne-Ni” means “Here I am,” a powerful declaration of the artist’s presence.

Hi-Ne-Ni Heart Sutra 1 by Peng Wei

Nearby, Soraya Syed’s Eternally Present pairs a digital film with a series of preparatory drawings. A model’s body becomes the site of exploration: calligraphic strokes are applied onto her body, and her movements — twisting and bending — generate new forms. The aesthetic of the calligraphic drawings recalls Arabic scripts, especially Al Thuluth, yet it feels alive with motion.

As a student of Arabic calligraphy, I’m stunned to encounter works by Iranian-born, New York–based artist Shirin Neshat. Her Offerings series presents three black-and-white photographs of a woman’s hands — closed, half-open, fully open — gestures that suggest prayer, surrender, defiance, and even communion. Persian poetry overlays the hands like a veil of ink, intimate yet carrying a sense of constraint.

The series originates from a 2019 wine label Neshat designed for the Ornellaia Wine Estate. Inspired by Omar Khayyam, whose verses appear on the photographs, Neshat explores wine as a symbol of shared life, reminding us that our brief time on earth is meant to be savoured.

As seen in the last few examples, calligraphy meets the modern human body much like cultural memory trying to settle on flesh that constantly grows, shifts, and resists containment. Perhaps the exhibition’s key takeaway is this: the development and future of women’s calligraphy, whether in Taiwan or beyond, is not linear. It expands through encounters, reinventions, and cross-cultural dialogues — along paths walked, those still being traced, and those yet to be taken.

Eternally Present by Soraya Syed

Offerings by Shirin Neshat

Reference:

Lu, H.-W. (2025, October). 策展人盧慧紋|自由自在?臺灣當代女性書藝家的處境與創作

[Curator Hui-Wen Lu: Free and Unbound? The Situation and Creative Practices of Contemporary Taiwanese Women Calligraphy Artists][Lecture]. Hengshan Calligraphy Art Centre, Taiwan.

Walking Their Own Paths: Women Calligraphers in Contemporary Taiwan is on view at the Hengshan Calligraphy Art Centre in Taoyuan, Taiwan, until December 1, 2025.