SILA: Celebrating Tatreez Between Tradition and Tomorrow

Tatreez, the Palestinian art of embroidery, is reimagined in SILA: All That Is Left to You, an exhibition where contemporary works explore heritage, identity, and the future of this time-honoured tradition.

Sense of Wander: ★★★★★

Inside Maraya Art Centre’s latest exhibition, SILA: All That Is Left to You.

SHARJAH, UAE — It isn’t every day that I come across an exhibition that stays with me long after I’ve stepped outside the gallery. SILA: All That Is Left to You, now on view at Maraya Art Centre, does exactly that.

SILA means “connection” in Arabic, and the exhibition traces the threads that bind individual and collective Palestinian voices through tatreez, a centuries-old art of embroidery. In Palestine, stitches on dresses, shawls, and textiles are never merely decorative. Recognised on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, tatreez functions as a living archive — its motifs carrying stories of place, identity, memory, and emotion. Colours speak, too: blue, for instance, often signals grief.

Over time, tatreez has also taken on the role of resistance. Practised by generations of Palestinian women — many of them refugees — it has helped sustain livelihoods while asserting cultural continuity. Even now, amid the ongoing devastation in Gaza, embroidery remains a way of holding on, of telling stories when so much else is being erased.

Upon entering SILA, I’m greeted by two Palestinian dresses richly embroidered with tatreez, alongside a display of embroidery samples by artisans from the Inaash Association. Founded in Lebanon in 1969 by Huguette Bechara El Khoury, Inaash has long supported Palestinian refugee women by preserving tatreez and providing income through handiwork. Several pieces in the exhibition emerge from collaborations between Inaash’s master embroiderers and contemporary artists, ensuring that the tradition remains both authentic and alive.

Embroidery samples by Palestinian embroiderers from the Inaash Association.

The oldest piece on view dates to 2010. In Our Mothers & Sisters, Palestinian artist Abdel Rahman Katanani shapes the figure of a seated woman from metal sheets salvaged from refugee camps in Lebanon — undulating materials often used for rooftops. She is depicted in the process of embroidery, and the fabric in her hands is real. The work belongs to Rula Alami, founder of the SILA exhibition series.

Our Mothers & Sisters (2010) by Abdel Rahman Katanani

One of the works I linger over longest is Liane Al Ghusain’s The People’s Day. On a cotton canvas, geometric tatreez motifs are arranged with measured precision. The cactus — stylised and ordered — are rendered in deep green to lighter green, encircling what the artist calls Temple of Steadfastness.

In Palestinian villages, cactus plants often border homes and fields, serving as natural defence. In tatreez, the motif symbolises protection and resilience, and is closely tied to patience: the Arabic word for cactus, sabbār (صَبّار), shares its root with sabr (صبر), or patience.

Exhibited alongside this work is Womb Amulets, where Al Ghusain enlarges bracelets once made by imprisoned Palestinian women as gestures of solidarity and friendship. Their form echoes shackles. The title recalls the brutal reality of women forced to give birth in prison cells, lending the work a devastating weight.

Temple of Steadfastness (2025) by Liane Al Ghusain

Nearby, a series of five cotton fabric descend from the ceiling in a spiral. From bottom to top, medicinal plants found in Palestine are carefully embroidered: Syrian rue, tumble thistle, sumac, bay laurel, and Syrian oregano. Titled Remembrance, the series by Farah Behbehani draws on ancestral herbal knowledge — each stitch resembling the act of planting, tending, and waiting. Regional motifs from across historic Palestine appear alongside the plants, forming what the artist describes as a woven record of land and lineage.

Aya Haidar’s Rooted takes memory on a sensory journey. A floor cushion embroidered with cedar trees, vine leaves, olive branches, and Jaffa oranges is filled with za’atar. As visitors press against it, the scent releases — earthy, familiar, and unmistakably Levantine. The work grounds the exhibition physically, anchoring memory in smell as much as sight.

Remembrance series (2025) by Farah Behbehani

Aya Haidar’s Rooted (2024) is displayed against a backdrop of embroidered handkerchiefs from her Resistance series (2025).

While tatreez traditionally lives on fabric, several artists expand it into new territory. In the Garden, by Amman-based Nagsh Collective, reinterprets embroidery on walnut wood, inlaid with brass to evoke a garden embedded with a bridal carpet.

Movement enters the space through Tala Hammoud Atrouni’s Frogs in the Pond. Metal beads shift on a movable tabletop, forming and dissolving patterns of tatreez. The work invites viewers to engage with the beads, letting their hands stir the patterns as they reflect on what it means for culture to hover between visibility and erasure.

In the Garden (2025) by Nagsh Collective

Frogs in the Pond (2025) by Tala Hammoud Atrouni

Some works confront you directly. In Weaving the Land Back, Areen Hassan unravels embroidered textiles into sculptural forms, threads extending in gestures that suggest both connection and rupture.

Samar Hejazi, on the other hand, suspends tatreez motifs in midair— embroidered without fabric, held together only by thread, their shadows falling softly on the walls and floor. This installation serves as a mirror of the Palestinian diaspora: a people sustained by one another, even when land is absent.

Weaving the Land Back series (2025) by Areen Hassan

Below the central motif, the Arabic phrase “Made in Jerusalem” is stitched with a biting sarcasm.

Transgressed Boundaries (2023) by Samar Hejazi

One corner of the exhibition is especially difficult to stand in. Katy Traboulsi’s replicas of war bomb shells are adorned with delicate tatreez. One is rendered in various shades of blue — a colour of loss and mourning in Palestinian embroidery. Beauty and violence collide, challenging us to confront the unsettling presence of beauty in something so viciously violent.

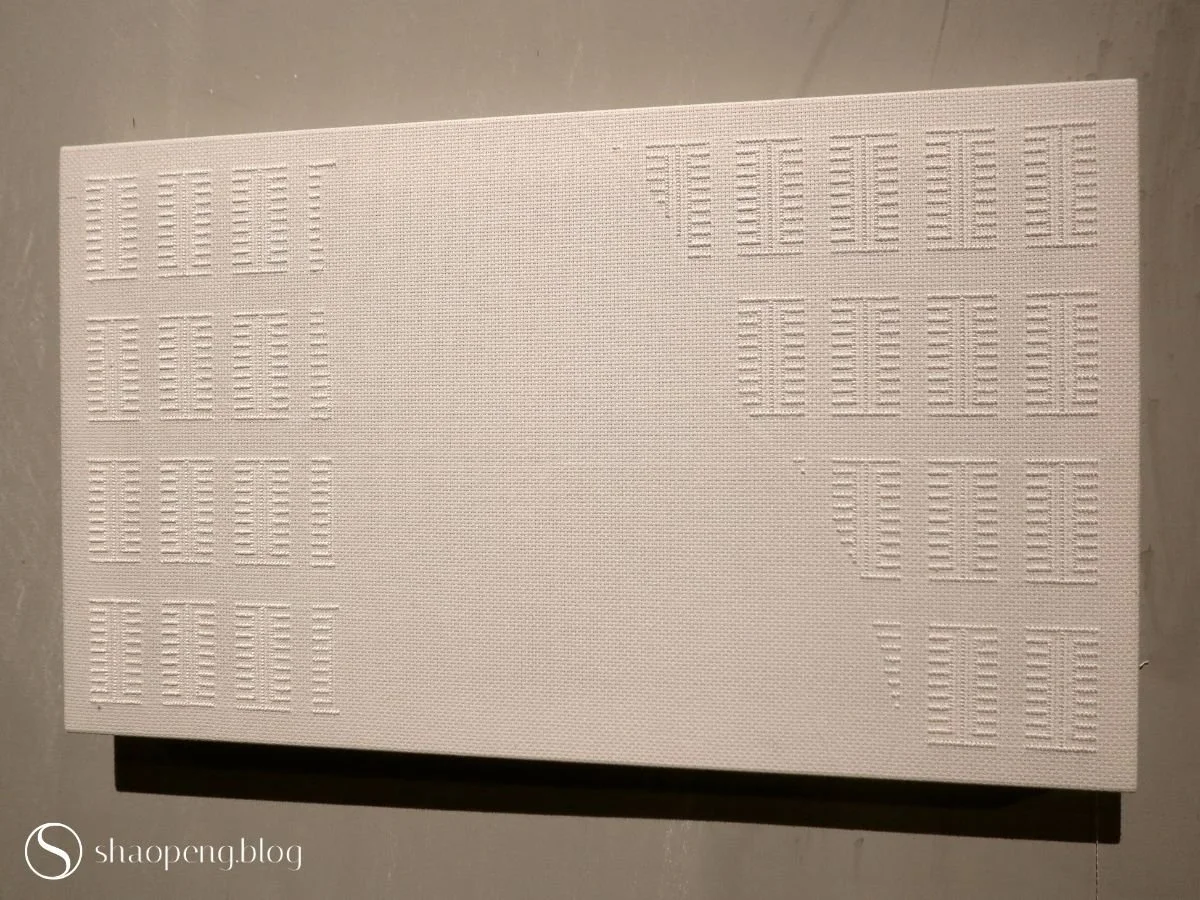

Behind them, ten canvases by Cristiana de Marchi appear blank at first glance. Only upon closer inspection do white threads reveal themselves. Each stitch marks the death of a child, a project that began in October 2023 and has grown alongside the rising death toll. Some spaces are left intentionally empty, allowing room for grief. This is also my first time seeing white-on-white embroidery.

Sound, too, becomes a carrier of memory in Nama AlMajdobah’s The Sound of Thread, where tatreez motifs are translated into melodies, allowing stitches to be heard.

Untitled (2025) by Cristiana de Marchi

Strength from the Perpetual Identities series (2025) by Katy Traboulsi

Amer Shomali’s Broken Weddings I (2025), composed of coloured spools of thread, poignantly depicts the many weddings that never took place.

Nada Debs’s furniture design is one of the exhibition highlights. The cabinet is covered in nakhla — the palm-tree motif — embroidered in a gradient from pale peach to deep red. Traditionally associated with the Ramallah region, the motif symbolises endurance and a deep connection to the land. Hand-embroidered by Inaash women onto rattan woven by men, the piece creates an intimate dialogue between genders and craft traditions.

Zaid Farouki’s The Dream of Return reimagines traditional Levantine women’s cap as a contemporary crown. Tatreez is found among silver coins from Palestine, a key from Jordan, and fabric from Syria. Each element speaks of displacement and belonging. Through this piece, Farouki asks: what should a Palestinian woman wear on her head today?

Nakhla (2025) by Nada Debs

The Dream of Return (2024) by Zaid Farouki

Like is a poignant installation by Palestinian artist Joanna Barakat that confronts the paradox of social media: what does it mean to “like” content that horrifies?

The work centres on a fabric draped over what resembles a child’s grave, embroidered with traditional patterns and repeating red hearts. In front of it stands a phone screen, simulating our gesture of swiping through posts and tapping “like.” The installation forces reflection on the irony and moral tension of engaging with images of extreme violence online: how can we continue to like content that brings grief, and if we don’t, how can we act to end the disaster?

Like (2025) by Joanna Barakat

Before leaving, it’s easy to miss a small detail: on the back of Nour Hage’s indigo-dyed textile, the phrase “to the children of Gaza” is embroidered in red Arabic script. Indigo, long associated with grief, makes the words feel even heavier.

The phrase pays tribute not only to the children who have lost their lives, but also to those whose right to a normal childhood — and adulthood — has been taken from them.

SILA makes it clear that tatreez is more than just embroidery. It is language, memory, resistance — and increasingly, a conduit for people around the world to engage with Palestinian heritage and culture.

Through contemporary artists working hand in hand with Palestinian embroiderers, the tradition is not only preserved, but given new life. The threads of tatreez bind past and present, heritage and tomorrow. And as I step back into Sharjah’s heat, that connection stays on, stitched firmly into my memory.

Study of a Cypress Tree (2025) by Nour Hage

On the back of Nour Hage’s Study of a Cypress Tree, the phrase “to the children of Gaza” is embroidered in red in Arabic.

SILA: All That Is Left to You is on view at Maraya Art Centre in Sharjah until January 5, 2026.